7 priceless artifacts you won’t find at the new Grand Egyptian Museum

The hotly anticipated new museum boasts some of the greatest treasures of antiquity. But there are some notable exceptions.

After more than two decades and with plenty of hiccups along the way, the Grand Egyptian Museum—colloquially, the “GEM”—finally officially opens in Cairo on November 1.

The halls of the museum are filled to the brim with priceless artifacts like the colossus statue of Ramesses II, Khufu’s ancient royal boats, and 5,000 treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb—which will be displayed together for the first time since the tomb’s discovery.

However, many other Egyptian artifacts of great historical and archaeological significance are notably not at the GEM. Whether scooped by foreign troops in Egypt, smuggled past officials, or claimed beneath the partage system, many antiquities were taken on behalf of former colonial powers who now display them in their museums across the globe.

Here are seven invaluable Egyptian antiquities you won’t see at the Grand Egyptian Museum—and why repatriation advocates would like them brought back.

1. The Rosetta Stone

Where to see it: The British Museum, London

When Napoleon’s soldiers laid eyes on the Rosetta Stone in 1799, they knew they’d found the key to decode hieroglyphics. On the desk-sized granodiorite stele were three clear scripts: ancient Greek, hieroglyphics, and demotic. “Like ‘democracy,’ demotic was the Egyptian script of everyday people,” explains American Egyptologist Bob Brier, a senior research fellow at Long Island University and author of more than 10 books on ancient Egypt.

Before the monumental discovery, many scholars believed hieroglyphics were merely pictograms. But the presence of the other scripts suggested otherwise.

While the Rosetta Stone’s actual words aren’t particularly interesting (they’re a public thank-you from the temple’s priest to the king for lowering taxes), its implications were enormous.

“It took another 20 years to translate the stone, and at that point everything cracked open,” says Brier, who calls the artifact “the most important find in the history of Egyptology.”

However, Egypt at the time was “like the Wild West,” says Brier, “and adventurers could go and take whatever they want.” French General Jacques François Menou considered the stone his personal property. The British disagreed and “eventually just pointed a gun at Menou and said give it to us,” says Brier.

By 1802, the Rosetta Stone was on display at the British Museum, where 19th-century visitors were free to touch the case-less stone. Despite ongoing efforts to repatriate the stone back to Egypt, it remains there to this day (behind glass, of course).

2. Luxor Obelisk

Where to see it: Place de la Concorde, Paris

Like Cleopatra’s Needles, the separated obelisks that now stand in New York City and London, the Luxor Obelisk in Paris is one half of a distinct pair. “Almost every New Kingdom temple had a pair of obelisks placed in front,” says Brier. (The New Kingdom, lasting from about 1550 to 1070 B.C., was ancient Egypt’s most powerful and prosperous period, also known as Egypt’s Golden Age.)

The Luxor Temple still stands on the Nile’s east bank, where millions of annual tourists cannot help but notice a conspicuous absence: “There’s just one obelisk there, looking sad like he’s missing his brother,” says Brier, who wrote Cleopatra’s Needles: The Lost Obelisks of Egypt.

The 3,000-year-old red granite monoliths represented victory to Napoleon, who didn’t have to loot the obelisks since de facto ruler Muhammad Ali Pasha gifted them to France in 1829. The problem? “Moving it was so difficult and expensive that the French decided to just take one,” explains Brier. France sent a thank-you gift in the form of the Cairo Citadel Clock, Egypt’s first public ticking clock, which promptly broke and couldn’t be fixed for 175 years.

3. The Dendera Zodiac

Where to see it: The Louvre, Paris

For two millennia, priests could look up to the ceiling of the Temple of Hathor to admire the Dendera Zodiac. Dedicated to Osiris and (possibly) commissioned by Cleopatra around 50 B.C., the eight-foot-wide bas-relief is one of the oldest known celestial maps and captures a fascinating merging of cultures.

“It’s an amalgamation of Greek and Egyptian thought—religion, science, technology—in the last dynasty of ancient Egypt,” says Salima Ikram, Egyptology professor at the American University in Cairo. Naturally, she adds, “it was much coveted by any and all who saw it.”

How did it get to Paris? There are competing narratives. The official story is that the French took it with permission from Egyptian officials in 1821. Others claim that antiquities thief Claude Lelorrain traveled to the temple located 40 miles north of Luxor with dynamite in hand to remove the Zodiac.

“From one of the most beautiful temples in Egypt, they just blasted it and hacked it to pieces,” says Egyptologist Laura Ranieri, founder of Ancient Egypt Alive, an organization dedicated to educating visitors about Egypt’s complex history.

Either way, the pieces were shipped off to King Louis XVIII, still irked that France had lost the Rosetta Stone, who paid an exorbitant 150,000 francs to install the zodiac in the Royal Library. A century later, it moved to the Louvre, where Ranieri says her tour groups are always awed and enthralled by the sandstone monument’s intricate details. The Temple of Hathor, meanwhile, installed a replica.

4. Sarcophagus of Seti I

Where to see it: Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

In the dark basement of three interconnected London row houses sits an artifact that, in 1817, nobody wanted: The sarcophagus of Seti I, an important pharaoh who died in 1279 B.C. and was buried in one of the deepest and most beautifully decorated tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

“Italian excavator Giovanni Belzoni brought it back from Egypt thinking the British Museum would buy it, but they foolishly didn’t,” says Ikram. Instead, for a bargain price of £2,000 in 1824 (about U.S. $250,000 today), the priceless 3,200-year-old sarcophagus sold to eccentric collector Sir John Soane who stashed it in his cellar. Preserved exactly as it was at Soane’s 1837 death, the house has since become a museum packed with eclectic oddities, though none eclipse the sarcophagus.

“It’s carved from translucent alabaster and was decorated with blue paint,” says Ikram. “So if you put a light inside, the whole thing glows and the blue figures look like they’re moving.” In 1825, 900 visitors got to see the sarcophagus’ eerie glow for themselves when Soane threw a three-day viewing party.

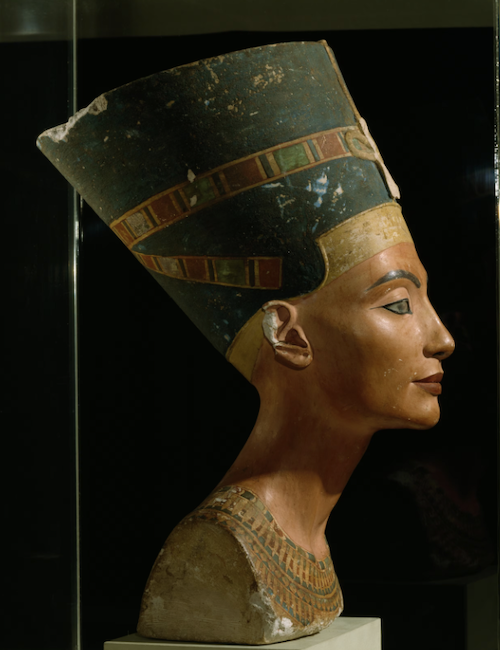

5. Nefertiti’s bust

Where to see it: Neues Museum of Berlin, Germany

In 1912, German-Jewish archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt spotted a female face while excavating the destroyed capital city of Akhetaten. “It was Nefertiti herself, lying face-up in beautiful condition,” says Ranieri, who was initially drawn to her field by the mysterious queen who may even have ruled as pharaoh. After her stepson Tutankhamun took over, Nefertiti’s image was deliberately defaced and destroyed.

Borchardt scored the miraculously intact artifact by downplaying its value and significance. “Borschardt said it was made of gypsum—just plaster, really—instead of precious limestone, which by then the law said had to stay in Egypt,” explains Ranieri. A deliberately obscure note on the bust from Borchardt’s excavation diary read, “Description is useless, must be seen.”

Eight years later, Nefertiti was on display in Berlin. The 18-inch, 20-kilogram bust wears a tall flat-cut wig, hand-painted in vibrant Egyptian blue and accessorized with red-and-gold ribbon. Egyptians immediately began negotiating to get Nefertiti back and were almost successful in 1929, although the deal was eventually vetoed by Adolf Hitler.

Now the bust has its own room at Neues Museum, where half a million museumgoers annually see what Ranieri hails “one of the greatest pieces of art in the world.”

6. Tarkhan dress

Where to see it: Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

The Tarkhan dress was found in 1913 at the Tarkhan necropolis, a massive ancient cemetery located 40 miles south of Cairo on the banks of the Nile. Initially considered a rag, the dress spent 60 years in an untouched box at University College London. When finally carbon-dated in 2015, the “rag” was revealed to be more than 5,000 years old—making it the oldest woven garment on the planet.

Despite its age, the well-constructed garment is in surprisingly good condition, notes Yale University Egyptologist and vintage fashionista Colleen Darnell: “The dress is made from three pieces of fabric with preserved delicate pleats of linen,” she says . Though its likely-floor-length bottom half has been lost, the dress’ top has a familiar V-neck and empire waist cut you could find at any modern-day H&M.

Compared to other remaining garments, like intricate wedding dresses worn once by someone important enough to preserve their ensemble, the size-2-ish Tarkham dress is significant in its ordinariness to regular Egyptians. And just like your old clothes, it’s got this relatable charm: “Stains at the armpits suggest this was a garment that was worn in life,” says Darnell.

Stains and all, the Tarkhan dress hangs in London’s Petrie Museum, named for British archaeologist Flinders Petrie, who in 1883 devised the “partage” system: From the French word to share, partage was essentially a deal to split artifacts 50/50 between foreign excavators and the excavated. Egyptian legislation finally ended the partage system in 1983.

7. Bust of Ankh-haf from Giza

Where to see it: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ankh-haf was both a prince and a vizier (or prime minister) in the 4th dynasty, revered for overseeing the building of the Great Pyramid and the Sphinx.

Excavated in 1925 during Harvard University’s massive 40-year expedition through Egypt and Sudan, this depiction of Ankh-haf was “a funerary bust that would have been in his tomb with him so his soul could be reanimated,” explains Ikram. Bad news for his soul: the partage system delegated the bust to American archaeologist George Reisner and then to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Ankh-haf’s bust is significant in its rare realism. “You can see a receding hairline and bags under his eyes,” says Ikram. From a culture that usually took plenty of liberties to portray pharaohs as perfect-looking gods, Ankh-haf is fascinatingly normal to look at. “He’s instantly recognizable as a real person,” says Ikram. “If you dressed him up in a suit, he could stroll down Fifth Avenue right now.”

Though Ankh-haf’s bust was acquired legally when gifted by the Egyptian government to Reisner in 1927, it didn’t happen without a dash of shady politics. East of the Great Pyramid, Reisner had also discovered the tomb of Hetepheres I—which was particularly remarkable as a royal tomb that was still intact. By then the law prohibited the looting of tomb, so Ankh-haf’s bust was a goodwill gift of sorts, saying thanks for not stealing our stuff.