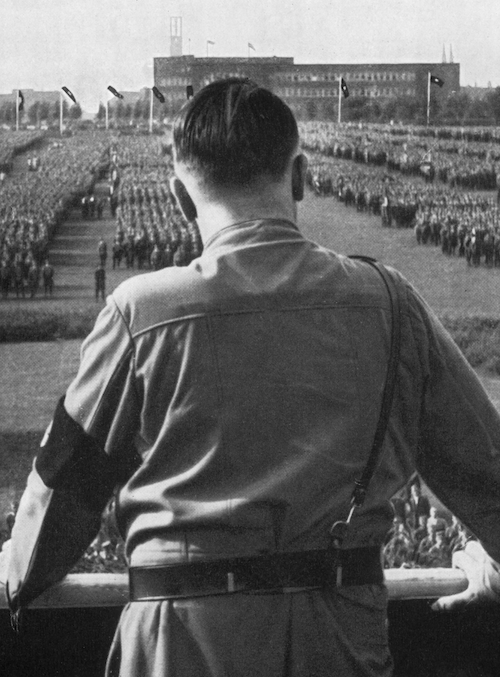

Hitler’s “Children”

The Führer never had kids, but these wild conspiracies insist otherwise

By all legitimate accounts, Adolf Hitler died on April 30, 1945, in his Berlin bunker after swallowing a cyanide pill and shooting himself in his right temple. At the chancellor’s side was Eva Braun, his young wife of one day, and their beloved German shepherd Blondi—both dead by cyanide. Their bodies were doused with gas and burned while Allied forces closed in on Germany’s capital from both sides. The war was over, and the führer was dead.

But what if he really wasn’t? Conspiracists have long speculated about if and how Hitler might live on: using a pseudonym in Argentina, huddling in a bunker under the Antarctic ice, or secretly siring offspring. Throughout his rise to power and reign, actually, rumors constantly swirled about Hitler’s romantic partners and possible progeny.

More than 80 years later, writers, creators, and fabulists in dark corners of the internet are still imagining ways and worlds where Hitler’s genes somehow survived. (See, as one example, Netflix’s upcoming remake of The Boys From Brazil, starring Jeremy Strong as a Nazi hunter who—50-year-old spoiler alert!—discovers a village of Hitler clones.) Where and how did these stories start? And why are we still obsessed with the idea of Hitler’s children?

The propagation of an “evil” gene

In June 1917, Hitler had a secret and brief affair with French teenager Charlotte Lobjoie, according to Lobjoie. The Telegraph reports that just before Lobjoie’s death in the early 1950s, she told her son Jean-Marie Loret the alleged truth about his father: The “unidentified German soldier” on his birth certificate was none other than Adolf Hitler. Lobjoie claimed she’d met a young Hitler as he sketched in a field in German-occupied France, had a brief relationship with him, and then, nine months after one “tipsy” night together, birthed an illegitimate son from whom she long hid her horrible secret. Per The Telegraph, German army papers reveal that envelopes of cash arrived for Lobjoie from SS agents.

For anyone of his generation with uncertain paternity, Loret’s story was a nightmare come true reflecting deep-rooted human fears. “The world was reeling after the war with questions about the source and nature of evil,” says Anthony Del Col, whose graphic novel Son of Hitler is very loosely inspired by Loret. For the record, Del Col—who wrote the book with Geoff Moore—believes Loret was “possibly, but very unlikely” to be Hitler’s child. “If Hitler had a son and knew about him, he’d have proudly paraded him around in a uniform,” he says.

Del Col’s imagined protagonist is Pierre, a French bakery assistant who learns Hitler is his biological father. “I…I’m nothing like him,” says Pierre, who struggles to control his innate anger, rage, and violence—qualities that perfectly reflect his father. “[The book] explores old questions of nature versus nurture,” says Del Col. “How much is he like his father? Is evil genetic? Can it be passed on?” Post–World War II, the existence and spread of evil across the globe was a real and serious concern.

While Son of Hitler takes plenty of creative liberty when the titular character is recruited to assassinate his famous father for the Allies, the fate of the real-life Loret isn’t so gallant. He went public with his sensational claims in 1977, penned the 1981 memoir Your Father’s Name Was Hitler, and considered claiming royalty rights to Mein Kampf. Loret died four years later, before DNA profiling may have proven (or disproven) his claims by comparing his genetic code to that of Hitler’s supposed remains—remnants of a skull and jaw bone said to be held in Moscow. In 2018, Loret’s son Philippe took a DNA test; however, there is currently no definitive proof that he is Hitler’s grandson.

“The scoop of the century or completely bonkers”

British socialite Unity Mitford traveled to Munich in 1934 with the expressed purpose of finding Adolf Hitler. The 20-year-old fascist spent 10 months sitting in Hitler’s favorite restaurant until the 45-year-old finally invited her to his table for all the usual reasons: “Unity was the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Aryan fantasy that Hitler loved,” says Phil Carradice, author of Hitler and His Women.

Mitford met with Hitler 139 separate times in four years and documented them all in her diary. (“The fürher and I have supper alone…. He makes me drink Champagne and I get drunk.”) But Mitford wisely never wrote about sex, if they had it—though their relationship was widely considered romantic by society gossip and tabloid magazines, who wondered if the couple would marry. To keep her nearby, Hitler paid for Mitford’s apartment in Munich.

On September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany, Mitford took the pearl-handled pistol Hitler had given her and shot herself in the head, ostensibly because of the impending conflict. “There aren’t many reasons a 25-year-old girl shoots herself,” says Carradice, “but unwanted pregnancy is certainly one of them.”

Miraculously, Unity Mitford survived the suicide attempt and returned to Britain amid a media scandal that’s still swirling. In the early 2010s, a British woman told a New Statesman journalist that her aunt was a midwife in 1940 when Mitford arrived in her ward. Afterward, she said, a baby boy was given up for adoption—implying that a now 81-year-old British man could be Hitler’s son. Deborah Mitford, the last of the Mitford sisters, dismissed the rumor as “village gossip.” A New Statesman editor described the claim as “either the scoop of the century or completely bonkers.”

Either of the above makes for a juicy story worth spreading. “Everyone knew about the Mitfords, and everyone talked about the Mitfords—especially the Mitfords,” says Carradice, who believes the nature of the family and the salaciousness of such a secret would have made it “virtually impossible” to keep.

A better rumor than the alternative

Despite ample chatter about Hitler’s love life, there are many holes in both Lobjoie’s and Mitford’s stories. Young Hitler was raised Catholic and didn’t believe in premarital sex; his notions of German genetic purity were also already formed, making him unlikely to sleep with people of other races (or even nationalities). The 40-something chancellor considered himself “married to Germany” and was adamant he never wanted children. All would make consummating a relationship difficult—but more difficult still, consummation might have been physically impossible for Hitler.

Speculation about Hitler’s genitals—and therefore fertility—was so rampant in his day, arguably thanks to Allied propaganda, that the rumor was immortalized in a walking march called “Hitler Has Only Got One Ball.” (The words are sung to the tune of the “Colonel Bogey March,” famously used in David Lean’s 1958 best-picture-winner The Bridge on the River Kwai.) Undescended testicles in infants aren’t rare; Johns Hopkins notes that cryptorchidism occurs in up to 5% of newborn boys. Recently discovered prison medical records from 1923 indicate Hitler might have had that condition, and other historians believe he had penile hypospadias, an abnormally located urethral opening.

Historians are fiercely divided, but Carradice believes these rumours are true. “I think Hitler was incapable of sexual intercourse,” says the Welsh author. “He had a very small penis, he had problems getting erections, and he had a libido so low he required medicine.” For a man of grandeur spouting the imperativeness of German propagation, such a condition would have been a bad and hypocritical look. Contrasting rumors of Hitler’s virility could have actually been very welcome, and such were never confirmed nor denied.

Alt-history is written by the victors

Hitler probably didn’t and maybe couldn’t have children. But just as people feared his possible survival, they also feared the notion that his hypothetical progeny could reappear to pick up where he had left off. Coming from a German writer, this imagined scenario has very different connotations than the same story from a British or North American perspective.

“It’s the winners who get the luxury of entertaining ourselves with stories of close calls and near misses,” says Gavriel Rosenfeld, Fairfield University history professor and author of The Fourth Reich. Alt-histories are like riding a roller coaster, he says: a safe and comfortable way for humans to experience controlled fear. As terrible and traumatic as the war had been, these stories serve to comfort people with the thought that things could be much worse.

As such, after what Rosenfeld calls the “too-soon period,” the Western world was bombarded in the ’70s and ’80s with “many dozens of schlocky novels and films with versions of [the same] what-if premise.” The endurance of Hitler’s genes featured prominently, however implausibly, in works like Ira Levin’s soon-to-be-remade The Boys From Brazil, where Hitler’s DNA is used to make 94 clones, or in They Saved Hitler’s Brain, where his severed head lives on to plot world domination. (More modern viewers might better recognize it from being spoofed, repeatedly, on The Simpsons.)

It’s only logical that as time passes, our alt-histories will change accordingly. “Hitler would have turned 100 years old in 1989,” says Rosenfeld. “The further we get from him being a threat, the more we’ll rely on his progeny to tell the same story.” Recent literature specifically is brimming with Hitler’s imagined children. Among them, we have Hitler’s Daughter by author Timothy Benford; (another) Hitler’s Daughter by Australian Jackie French; Siegfried by Harry Mulisch, from the Netherlands; Hitler’s Secret by British writer William Osborne; and Winnie and Wolf by Britain’s A.N. Wilson.

All of the above borrow from long-standing rumors that Hitler procreated, but all are united in their ultimate condemnation of the führer. “Nobody will publish anything with even a hint of generosity toward Hitler,” says Del Col. “That’s why we’ve got Hitler being strangled right on our book’s cover. People want to know Hitler’s gonna die.”

The offspring we’re not talking about

Throughout a near century of nonstop conjecture about Hitler’s genes, few are keen to acknowledge the biological truths we do know: Living descendants of the Hitler family are indeed alive and well. Journalist David Gardner tracked them down for his 2023 book, The Hitler Bloodline.

The book begins with a helpful family tree showing that Adolf was the fourth of six children. Only two of them lived to adulthood, and neither had children of their own. But Hitler also had two older half-siblings, Alois and Angela, who between them had five children—Hitler’s nieces and nephews. One fought and died for the Nazis; another denounced his uncle, moved to America, and fought for the US Navy. According to Gardner, three American men currently carry Hitler’s bloodline, though they’ve long changed their birth names (one of them was born “Alexander Adolf Hitler”) and denounced their infamous great-uncle.

Gardner writes of yet another rumor going strong: “I was told by an impeccable source that the three surviving Hitler brothers, all living in a New York suburb, have agreed never to marry or have children to ensure the Hitler gene died out with them.” One of the brothers told Gardner that such a pact was an exaggeration. Nonetheless, none fathered children, meaning Hitler’s bloodline will indeed definitively end after this generation. That is, unless you believe the rumors.