An Archivist Uncovers the Real Story of a Royal Love Affair

In a Q&A, Jane Marguerite Tippett talks about finding a trove of notes about King Edward VIII

In Once A King, archivist and author Jane Marguerite Tippett lived a historian’s dream come true. While researching a different book on King Edward VIII, an unassuming footnote led her to an uncatalogued archive of recorded interviews with his wife, Wallis Simpson, where the Duchess of Windsor answered questions from a man called “Charlie.” He turned out to be Charles J. V. Murphy, a little-known American journalist for Life magazine who was the ghostwriter of the King’s 1951 memoirs, written 15 years after he abdicated the throne to marry Simpson. When Tippett learned there was a trove of the Murphy’s papers at Boston University, she packed her bags and headed to Massachusetts.

Tippett’s heart raced when she saw the 17 boxes of papers and notes: Four were entirely devoted to the Windsors. Among them were unedited first drafts, hundreds of pages of interview notes with Edward and his closest advisers, Murphy’s typed diary entries chronicling the four years he shadowed the couple after Edward’s famous 1936 abdication. There were even hand-written pages by the Duke himself, on swanky Waldorf Astoria stationary, no less.

To recap: Upon his father George V’s death in January 1936, 41-year-old Edward became King. The new monarch was a hard-partying bachelor with a string of affairs, including one with then-married Simpson, an American socialite who’d already been divorced once. Once Edward took the throne, Simpson divorced her second husband. In December, the two were engaged and all hell broke loose. British PM Stanley Baldwin deemed the match politically and morally inappropriate, and his government required the King to resign should they marry. Edward chose love over duty: Upon abdication, the one-time King became the Duke of Windsor and married Simpson in 1937, making her a Duchess. His throne went to his brother, George VI, who’d then pass it to Elizabeth II.

In arguably the first royal tell-all, Edward desperately wanted to get his story out to the world and “omit nothing however secret and personal.” But A King’s Story ultimately bowed to pressure from the monarchy; much of the Duke’s more personal stories were edited out before its 1951 publication. Like the memoir’s counterpart, Simpson’s 1956 book The Heart Has its Reasons, his title gave little insight into the abdication scandal and no mention of the questions that have fascinated the world for almost 90 years: Why did the one-time British King give up his powerful throne for love? And was it worth it?

Zoomer reached Tippett at her home in New York – where a framed original photo of Edward is displayed among her family photos – for a Q&A on how she discovered his original letters and papers and what pop culture gets wrong about the scandalous couple, nearly a century later.

Rosemary Counter: Am I crazy or is that a picture of King Edward on your table?

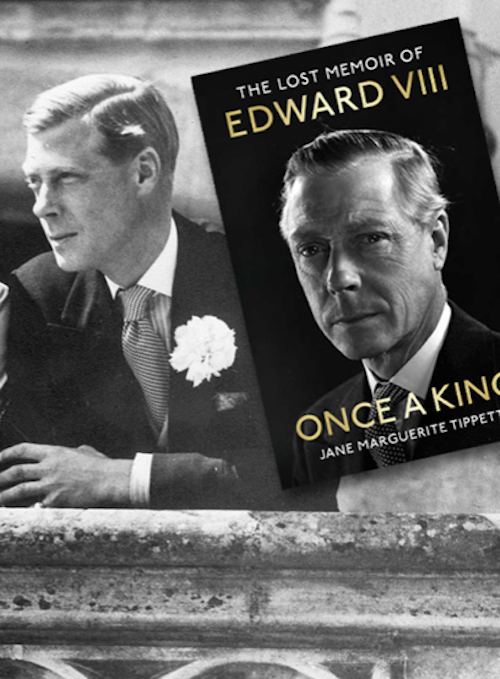

Jane Marguerite Tippett: It is! That’s an original print by Philippe Halsman, the preeminent Life photographer in the ’40s and ’50s, and now the cover of my book. When I first started working on this, I was Googling around and it came up from a photography dealer. It’s from a session in November 1947 in anticipation of a Life article, but they didn’t end up using them. They decided to use a dual portrait of Edward and Wallis instead. But it’s an incredible print, and it’s mine now.

RC: So you love Edward enough to frame him and put him there with your other family photos?

JMT: Yeah, he’s right there beside my grandmother! It’s more of a souvenir of the book though.

RC: A book that almost never was.

JMT: It started by looking at 1937, the year after the big year of his life,1936. I thought that year would be fundamental to shape the remainder of his life and exile and all the emotional fallout from his family that reverberated for the rest of his life. That was also the year he famously visited Germany, in October – two weeks that define how we see Edward. I don’t think he was a Nazi sympathizer,I think his political outlook was firmly in the direction of appeasement. I think he admired the industrial rejuvenation that Germany had accomplished in the same way he admired it in the States under FDR. He had thriving relationships with FDR, with Churchill. He met with Truman. None of these “great men” of history ostracized him, so I don’t think he was a Nazi.

RC: Do you think it was a smear campaign since he abdicated anyhow?

JMT: No, because the ideas of Edward as a Nazi don’t take a life of their own until after both his and the Duchess’ death. Since then, their legacy has been up for grabs, since there’s no one around to sue them for libel. They don’t have heirs, so there’s no one to claim or protect them.

RC: Maybe that’ll be … you?

JMT: I literally stumbled on this while working on a very different book when I thought, gosh, I wonder whatever happened to their ghostwriter? I would love to make myself sound like some kind of history sleuth, but it was no more complicated than just asking the right questions. Murphy had worked with them for close to a decade, and his papers were just sitting there at Boston University. I hope I do, but I’m not anticipating ever having that research experience again. It’s what historians dream of.

RC: On one hand, it’s lucking out – like finding a needle in a haystack. But on the other, it was all just sitting there waiting to be discovered by whoever got there first.

JMT: I think it’s because at some point we stopped asking real questions about Edward Windsor. We started treating him as a tabloid-esque figure and stopped looking beyond the enshrined narrative. People figured Murphy had said everything he could in the book, when in fact the book was heavily redacted.

RC: If this were a film, you’d be looking at the stuff on the cutting-room floor. What’s the benefit of that material to you?

JMT: Unlike most writers, Edward wanted to create material that he had no intention of ever actually publishing. He wanted to leave a historical record for the future. So while he was very careful in his [published] memoirs, he wrote much more freely in his notes. That right there is very interesting and significant. There were so many considerations that went into the book. He was very concerned about protocol and very hesitant about what his family would think and say. He had advisers in England who were constantly cutting things out. The memoir ended up being more like a record and not personal at all.

RC: Wallis Simpson comes across as a lot more likable than history has painted her.

JMT: I find her exceedingly approachable, direct. There’s a great interview with the BBC on YouTube where she’s relaxed and authentic. People have really made up their minds about herand have been resistant to the facts that actually tell a different story. One of my favourite finds in the archive was a bullet-point list in Edward’s hand about Wallis’ defining characteristics: “Independent, exacting, perfectionist.” He really saw her and loved her and admired her. [Otherwise], there’s a real lack of empathy for her, a failure to appreciate what it was like to live the rest of her life as the woman who caused this debacle.

RC: It reminds me a bit of Yoko Ono, and like John Lennon it seemed that Edward wanted out long before she was around.

JRT: I’m not sure he wanted out, but he wanted it differently. He wanted to be a Royal in a very different way, a very modern way. There’s something incredibly modern about Edward and his approach to monarchy, which is exactly the approach that’s been adopted now: informal, direct, efficient. These things antagonized his contemporaries but it’s exactly what modern monarchs are doing. And he was the first celebrity Royal, literally movie-star famous just as the Hollywood system was blowing up. He did what he could to revise the role but he hit a wall with his marriage. That’s when he decided he was done. But it was very much his decision and she was more of a bystander.

RC: You sound like you could just as easily be talking about Prince Harry.

JRT: There are parallels, yes, but there are big differences. Edward left because of things that Harry was given. Harry was allowed to marry, to work, was given a home. But both came up against a system they can’t change and were unable to continue living inside. It says a lot to me about the monarchy that they keep losing their most charismatic and innovative individuals. They can’t seem to find a negotiation between individuality and The Firm.

RC: Edward was only king for 10 months. Why are we obsessed still?

JRT: It was a moment that represented an important transition into modernity. Suddenly fulfillment of self was more important than fulfillment of convention and tradition. He chose personal satisfaction over duty. The audacity surprised people – we’re still shocked by that decision. Who gives up the throne for love? At the same time, if you had to quit your job to be with the person you love, of course you would. That he was charismatic and handsome helped too. The whole thing played out like a great Hollywood love story.