“We were all delighted today to get your letter”

A collection of letters between a private and his mother offer an intimate look at life at war—and at home

On Aug. 9, 1916, William Shaw Antliff penned a thank-you letter to his mother, Ruth Caroline Shaw Antliff, in Montreal. “My dear Mother,” he began as always. “You are all going to such a lot of effort sending me things that the very least I can do is write a letter of thanks.” The 20-year-old McGill-student-turned-soldier wrote from somewhere in Belgium, endlessly grateful for care packages of handkerchiefs, boot laces, spending cash, warm underwear, knitted socks, magazines, candy and cakes. “We can’t get things like this around here and they are singular gold mines to us.”

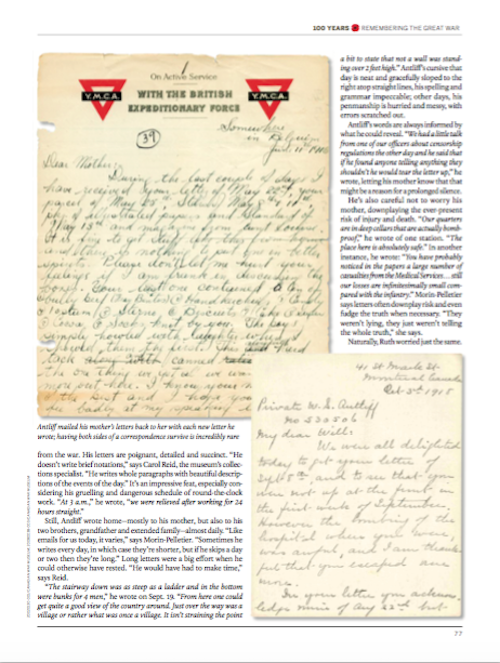

Like so many of the more than 400,000 Canadian soldiers who served overseas during the First World War, Antliff corresponded often and enthusiastically with his family on the home front. But unlike almost everyone else, he had a unique habit of returning the letters they sent to him. “I am sending the letter back enclosed in this one,” he wrote before signing off, “with love from Will.”

With 239 letters he wrote and mailed over three years, he returned 434 more back home to Montreal. Saving and storing the letters was so odd that Antliff’s mother, a 44-year-old widow and mother of three maintaining the family home at 41 Mark Street, considered the gesture overkill. “At one point she even writes, ‘Why do you want me to keep these? They’re not of interest to anyone,’ ” says Mélanie Morin-Pelletier, historian at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. But it’s fortunate he persisted. The letters are of great interest to Morin-Pelletier and visitors to the museum’s archives—from primary school kids to authors working on books—for the simple fact that both sides of the correspondence have survived a century. “Having the mom’s letters too almost never happens,” explains Morin-Pelletier.

Tens of thousands of Canadian families maintained contact during the war via the Canadian Postal Corps, a service especially created in 1911 to move military mail. In 1915, Canadians sent more than eight million letters to their relatives in the military, who in turn posted nearly four million home.

Among those letters were Antlff’s. He was an Ottawa-born anglophone in Quebec who put his business studies on hold to serve with the No. 9 Canadian Field Ambulance. His military medical records note he was five foot nine and 128 lb., fair with light brown hair and blue eyes, with an appendix scar but no smallpox marks. He departed from Saint John, N.B., for Bramshott, England, and arrived in France in April 1916. “His job was on the front lines, going onto the battlefield to get wounded soldiers and bringing them back for emergency treatment before they were sent to hospital,” says Morin-Pelletier. The war marked the first major conflict in which automobiles were used to transport the wounded, and Antliff’s unit rescued wounded Allies as well as German soldiers (or as he calls them, “Fritzys”). “Out of four wounded men I carried to the truck-line three were Fritzys,” he wrote on Sept. 26, 1916. “One had been out in No-Man’s Land for 8 days.”

When he wasn’t working, Antliff was a thoughtful and prolific writer who diligently described the realities of war: “We’re only a mile and a half or two miles from the front here and our worst fear is from gas. The guard’s job is no joke because he has to give the signal and get everyone up,” he wrote. “When the gas really starts all the sirens in the place are set loose at once. The guard has then to cover the basement windows with blankets which are all ready just to be pulled over.” At the same time, Antliff can see beauty and serenity when it peeks through: “Yesterday morning when I came out in the court-yard the sun was shining brightly, a couple of kittens were playing together and the birds were singing along the roof. Things seem the opposite of war-like and I don’t believe you people in Canada realize how quiet it is most of the time.”

Other times are far more dramatic: “There were about 14 or 15 of us started out in single file. As we had to go overland owing to the state of the trenches the leading man carried a large Red Cross flag. The mist was so thick one couldn’t see 100 yards in front,” he wrote. “All around the ground was covered with signs of a battle. Duds, hand grenades, equipment thrown away, steel helmets (both ours and Fritzy’s), gas bags and in fact all kinds of souvenirs if one could carry them.”

Antliff’s writing is a rare treat that stands out among other letters from the war. His letters are poignant, detailed and succinct. “He doesn’t write brief notations,” says Carol Reid, the museum’s collections specialist. “He writes whole paragraphs with beautiful descriptions of the events of the day.” It’s an impressive feat, especially considering his gruelling and dangerous schedule of round-the-clock work. “At 3 a.m.,” he wrote, “we were relieved after working for 24 hours straight.”

Still, Antliff wrote home—mostly to his mother, but also to his two brothers, grandfather and extended family—almost daily. “Like emails for us today, it varies,” says Morin-Pelletier. “Sometimes he writes every day, in which case they’re shorter, but if he skips a day or two then they’re long.” Long letters were a big effort when he could otherwise have rested. “He would have had to make time,” says Reid.

“The stairway down was as steep as a ladder and in the bottom were bunks for 4 men,” he wrote on Sept. 19. “From here one could get quite a good view of the country around. Just over the way was a village or rather what was once a village. It isn’t straining the point a bit to state that not a wall was standing over 2 feet high.” Antliff’s cursive that day is neat and gracefully sloped to the right atop straight lines, his spelling and grammar impeccable; other days, his penmanship is hurried and messy, with errors scratched out.

Antliff’s words are always informed by what he could reveal. “We had a little talk from one of our officers about censorship regulations the other day and he said that if he found anyone telling anything they shouldn’t he would tear the letter up,” he wrote, letting his mother know that that might be a reason for a prolonged silence.

He’s also careful not to worry his mother, downplaying the ever-present risk of injury and death. “Our quarters are in deep cellars that are actually bomb-proof,” he wrote of one station. “The place here is absolutely safe.” In another instance, he wrote: “You have probably noticed in the papers a large number of casualties from the Medical Services . . . still our losses are infinitesimally small compared with the infantry.” Morin-Pelletier says letters often downplay risk and even fudge the truth when necessary. “They weren’t lying, they just weren’t telling the whole truth,” she says.

Naturally, Ruth worried just the same. “My dear Will,” she wrote in October 1918. “We were all delighted today to get your letter of Sept 8th and to see that you were not up at the front in the final week of September. However the bombing of the hospital where you were was awful and I am thankful that you escaped.” Always trying to stay positive, Ruth was relieved her other two sons were too young to enlist, and that William served with the Field Ambulance rather than the air service. “I still think it is the most dangerous job of all,” she wrote.

Though Ruth’s letters might initially seem the less exciting half of the Antliff collection, both Reid and Morin-Pelletier say their survival is what makes the correspondence especially significant. “We learn what it’s like to be a soldier’s mom, how stressful it was and how helpless she felt,” says Morin-Pelletier. “Even when she gets a letter, by that time it’s been a week or two and she doesn’t know if he’s still alive.”

Ruth closely follows the newspapers, and reports war news to Antliff just as o en as he does to her. “You cannot imagine what a shock it was to me to hear about Steve—I had not heard that he is missing before your letter,” she wrote, before delivering bad news: “They think he was killed. It was on Aug 10th that it happened. Steve went over the German lines for the first time—he was alone in his machine ying with 9 other aviators. There were clouds in the sky and suddenly a large group of German planes appeared above them and dropped bombs. One hit Steve’s machine and it went down behind German lines, out of control.”

How much Ruth knew is a fascinating glimpse into life on the home front. “The Canadian side of the story illustrates what type of information was being sent overseas,” says Reid. Ruth was also part of a network of soldiers’ mothers who met regularly to trade information. “She tells stories about the mothers meeting to sit around the table with their sons’ letters,” says Morin-Pelletier. “They’d take out a big map and try to figure out where their sons were serving. Vimy and Passchendaele resonate for us today, but then they were random places nobody knew.”

Ruth gives equal ink to the mundane details of daily life—a comfort to her son, no doubt. “Grandfather has a cold but all others are well,” she wrote. Likewise, despite the weight of the war, her son is still concerned with smaller things: “I am awfully sorry I forgot Donald’s birthday,” he wrote.

Ruth also writes about fundraising with the Methodist church, knitting, preparing comfort packages for soldiers and making do with ever increasing restrictions on household supplies. “We are going to have a hard time this winter over the shortage of coal,” she wrote. “Each household is only allowed to have 70 per cent of what they always burn in the win- ter and inspectors are now going from house to house to see the coal in the cellars. If anyone is found hoarding, the coal will be taken.” Bitterly cold Montreal winters made this situation not just uncomfortable, but dangerous. “I feel sure all the sickness and Spanish flu we have with us is due to the fact that all the houses are so cold and damp with no fires and such terrible cold wet weather.” She also writes of flour and sugar shortages, making her care packages of candy to her son particularly special.

On Nov. 11, 1918, Ruth finally got to pen good news: “This is a most wonderful day—the long looked for day of peace and our hearts are full of joy and thanksgiving.” The war was over, and her son had survived. He arrived home via Halifax in March 1919. In August, he was awarded the Military Medal. He married in 1924 and had three children. He relocated to Toronto to work as the general manager of Canada Bread Company, where he lived until his death in 1985 at age 88. He’s buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto, and his obituary says he left 12 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Details of the donation of his archive of letters are private, but someone from his immediate family offered the letters to the museum. “They illustrate what’s important to them: family, friends, daily life at home,” says Reid. “You can almost imagine him sitting in a trench or a dugout writing up the day’s events.”