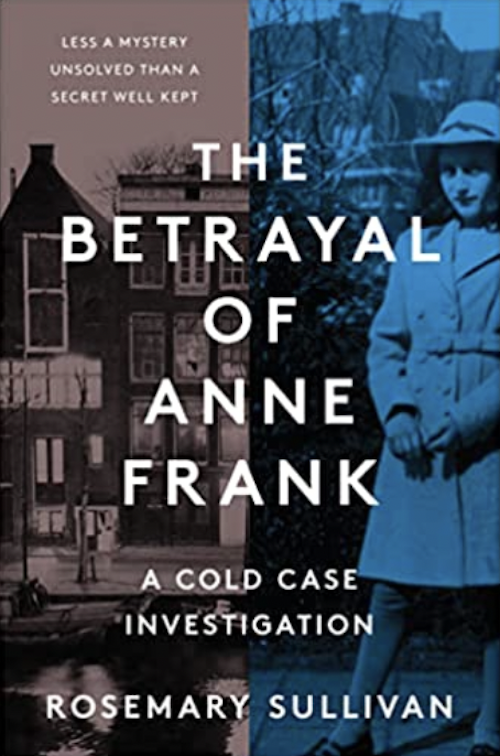

The Betrayal of Anne Frank

An investigation into who revealed the diarist’s Amsterdam hiding place to the Nazis

Canadian biographer Rosemary Sullivan’s controversial book took her to Amsterdam on an assignment like no other: Meet the cold case team, headed by retired FBI agent Vincent Pankoke, and report on their investigation into who exposed Anne Frank’s hiding place in the secret annex of a canal-side warehouse. After the Nazis found eight people, including the young diarist and her family, on Aug. 4, 1944, they arrested and deported them. Her father, Otto Frank, was the only one to survive; Anne, 15, and her sister Margot died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation is a heartbreaking, harrowing look at the painstaking process that led an international team – including data analysts, historians and criminologists – to conclude a Jewish notary, Arnold van den Bergh, was the leading suspect in the 78-year-old mystery. Zoomer speaks to the author about the project and her process.

Rosemary Counter: Congrats on the new book. You’ve kept me up for, like, three nights in a row. It’s intense.

Rosemary Sullivan: It is rather intense, yes. I did cry a couple of times. It was very painful for me to replicate the image of Anne at the camp, for example. It was hard to write, but I’m essentially a storyteller, and these stories need to be told. After I wrote Stalin’s Daughter in 2015, the editors at HarperCollins approached me in conjunction with the cold case team. I’m still, as most of us are, totally fascinated with the Second World War. For my generation, there’s a legacy of reading Anne Frank when you’re 12 years old.

RC: My generation too! Anne Frank is pivotal when you’re 12. I thought I knew the story pretty well, but your book proved to me I really don’t. Last week I would have sworn she was Dutch — she’s German.

RS: Well, she was Dutch too, having moved at four years old. These kinds of details get lost sometimes. I didn’t realize that Otto Frank had tried so hard to get visas. He tried to go to the U.S., to Cuba, anywhere. I was struck by the way his agency — which was once very powerful — was taken from him, step by step. I’m so inspired by Otto Frank, who was determined to turn total tragedy into something redeemable. He published Anne’s diary because it was a flash of light in the darkness. Like him, I want people to read this book and let it be a warning. An occupation like the one in Amsterdam could absolutely happen now.

RC: It’s very tempting to think of the Second World War as a long time ago. I don’t know if that’s the way we teach history, or the media, or human nature, or what.

RS: There was a time in Amsterdam when I visited a theatre where Jewish prisoners were collected and held before transport to the camps. Upstairs, they had a visual map where you could press a button and it showed the locations of the captives. Beside me, there was a tall man in his 80s, and he pushed a button and said, “that’s me.” He had been four years old when he was one of 50 children taken captive. So before I looked at the investigation, I needed readers to remember and understand how that could happen and what those years from 1933 to 1944 were like. Then we could start discussion various situations.

RC: The book narrows many situations down to 12 major suspects—The Nanny, The Greengrocer, The Dutch Notary, etc. — and then looks at their “knowledge, motive and opportunity.” Tell me about this process?

RS: Take the example of Nelly Voskuijl, the sister of one of the Frank Otto’s helpers, Bep. We ask first: Could she have known there were Jews hiding there? How? Could she have overheard, or seen Bep collecting food? But all of this is hypothetical, of course. The next consideration is motive. Could she have been angry at her sister? Did she seek an in with the Germans? Finally, opportunity. Was she in Amsterdam at the time of the betrayal?

RC: Recent years have seen primary sources digitized and archived. How did that change the investigation?

RS: That’s a question for Vince, and certainly the Dutch were great record keepers to begin with, but I can tell you without AI technology they could never be so thorough. When a name or address pops up, Vince could immediately cross-reference it in the database. Everything was uploaded, for instance an arrest warrant or membership cards, and all that info would be entered too. Now you can see who’s where, and when, and the connections between residents. In the immediate vicinity of the Annex, you can see the addresses of who’s Jewish, who’s an informant, who are Dutch Nazis. It was very impressive.

RC: Yet at the same time, you also document old-fashioned manual labour, like when the team digs through 1,000 dots from a hole-puncher trying to match yellow paper.

RS: These detectives are obsessive. And you’d never guess it. Vince is like your really nice, quiet uncle.

RC: Who takes you aside and says, “Would you mind sorting these holes for me? I just need the yellow ones and I’ll give you 10 dollars.”

RS: There were a lot of young researchers on the team to who deserve to be acknowledged. My job was just to write it, to bring the cold case and these people to life.

RC: When you’re humanizing these people, are you at all apprehensive about — I don’t know how to say this nicely — making the Nazis sympathetic characters?

RS: To me, evil starts at the top. There are people in this book that are viciously cruel. There are people lower down who are making money on the people they betray. There are people who begin helping the resistance and then become informants. Many people betrayed Jews only because their own family’s life was on the line. It was so hard to learn that the most likely candidate for betrayal was in fact Jewish himself. I understand this could be painful for the Jewish community and fodder for the anti-Semitic community. Still, he’s a very tragic figure for me.

RC: And turns out Otto Frank knew and protected the identity of the informant. Why?

RS: Otto Frank didn’t want to hurt the children of this man. We interviewed his granddaughter, and as you can imagine, it’s complicated. Who wants to be the grandchild of the man who betrayed Anne Frank? We’ve considered this very carefully before we published the book.

RC: Why do we need to know his name? Does it even matter?

RS: No, I don’t think it does matter actually. There is so much more accountability than that of the betrayer; there’s accountability of the Netherlands, of the international community that turned Otto Frank and six million other people down for visas; for those who chose sides and those who did nothing. Once the investigation reached its conclusion, once we had the name and his reasons, either you throw it all out or you decide the truth is important.