Fit to be tied

Tubal ligations are a one-time, low-risk way to forever free yourself from sticky creams, foreign devices, too easily forgotten pills—and the fear of unwanted pregnancy. But the permanence of the decision can create a battleground between women and their doctors.

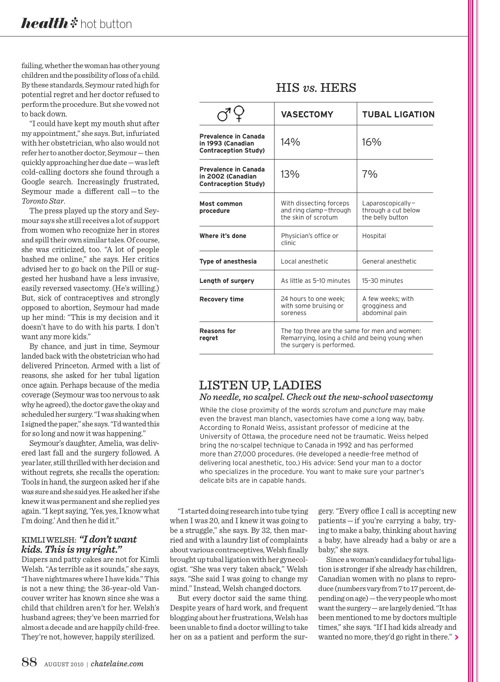

IN CANADA, TUBAL LIGATION—or “getting your tubes tied”—is the contraceptive method of choice for 7 percent of Canadian women of child-bearing age, according to the 2002 Canadian Contraception Study. The procedure, which clamps or clips the Fallopian tubes to prevent eggs from moving into the uterus, is more than 99-percent effective and is covered by insurance. But while most women are satisfied with the result, some experience regret, especially if a change in circumstances prompts them to rethink their decision to be sterilized. Doctors may feel conflicted about performing tubal ligation for this reason. The procedure can be reversed, but that means more surgery and it can be pricey. And there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to conceive afterwards. So how do you know if it’s right for you? Three women share their stories.

TARRAH SEYMOUR: “I don’t want any more kids.”

Twenty-two-year-old Brampton, Ont., resident Tarrah Seymour always wanted to get married and have two children while she was still young. When she met her future husband on the first day of college orientation, she didn’t waste any time making it happen. Princeton, now a shy toddler obsessed with toy cars, was born a week before graduation. When baby number two arrived, Seymour’s husband opted to stay home as she started a new career in security at a local superstore.

The last step of Seymour’s plan was tubal ligation. Like her mother, she wanted the procedure immediately after her scheduled Caesarean section. To her it made sense: It would take just a few extra minutes, she would already be in the operating room, she wouldn’t have to recuperate twice, and she didn’t want any more kids. But when, at a regular appointment, she asked her OB/GYN to perform the surgery, he refused. “He just said no right away,” says Seymour. “He said, ‘You’re too young and I won’t do it.’”

Like many Canadian doctors, Seymour’s obstetrician was wary about sterilizing someone so young. Since there are no guidelines for the procedure—the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada is currently drafting them, but they won’t be available until next year—most doctors screen candidates on a case-by-case basis to try to determine the likelihood of regret. Doctors take into account a patient’s age, any risk associated with a postpartum surgery, the odds of the current relationship failing, whether the woman has other young children and the possibility of loss of a child. By these standards, Seymour rated high for potential regret and her doctor refused to perform the procedure. But she vowed not to back down.

“I could have kept my mouth shut after my appointment,” she says. But, infuriated with her obstetrician, who also would not refer her to another doctor, Seymour—then quickly approaching her due date—was left cold-calling doctors she found through a Google search. Increasingly frustrated, Seymour made a different call—to the Toronto Star.

The press played up the story and Seymour says she still receives a lot of support from women who recognize her in stores and spill their own similar tales. Of course, she was criticized, too. “A lot of people bashed me online,” she says. Her critics advised her to go back on the Pill or suggested her husband have a less invasive, easily reversed vasectomy. (He’s willing.) But, sick of contraceptives and strongly opposed to abortion, Seymour had made up her mind: “This is my decision and it doesn’t have to do with his parts. I don’t want any more kids.”

By chance, and just in time, Seymour landed back with the obstetrician who had delivered Princeton. Armed with a list of reasons, she asked for her tubal ligation once again. Perhaps because of the media coverage (Seymour was too nervous to ask why he agreed), the doctor gave the okay and scheduled her surgery. “I was shaking when I signed the paper,” she says. “I’d wanted this for so long and now it was happening.”

Seymour’s daughter, Amelia, was delivered last fall and the surgery followed. A year later, still thrilled with her decision and without regrets, she recalls the operation: Tools in hand, the surgeon asked her if she was sure and she said yes. He asked her if she knew it was permanent and she replied yes again. “I kept saying, ‘Yes, yes, I know what I’m doing.’ And then he did it.”

KIMLI WELSH: “I don’t want kids. This is my right.”

Diapers and patty cakes are not for Kimli Welsh. “As terrible as it sounds,” she says, “I have nightmares where I have kids.” This is not a new thing; the 36-year-old Vancouver writer has known since she was a child that children aren’t for her. Welsh’s husband agrees; they’ve been married for almost a decade and are happily child-free. They’re not, however, happily sterilized.

“I started doing research into tube tying when I was 20, and I knew it was going to be a struggle,” she says. By 32, then married and with a laundry list of complaints about various contraceptives, Welsh finally brought up tubal ligation with her gynecologist. “She was very taken aback,” Welsh says. “She said I was going to change my mind.” Instead, Welsh changed doctors.

But every doctor said the same thing. Despite years of hard work, and frequent blogging about her frustrations, Welsh has been unable to find a doctor willing to take her on as a patient and perform the surgery. “Every office I call is accepting new patients—if you’re carrying a baby, trying to make a baby, thinking about having a baby, have already had a baby or are a baby,” she says.

Since a woman’s candidacy for tubal ligation is stronger if she already has children, Canadian women with no plans to reproduce (numbers vary from 7 to 17 percent, depending on age)—the very people who most want the surgery—are largely denied. “It has been mentioned to me by doctors multiple times,” she says. “If I had kids already and wanted no more, they’d go right in there.”

On the other hand, should Welsh’s husband choose to have a vasectomy, he could easily get one. Though it is also down to a doctor’s discretion, male sterilization in Canada is done at twice the rate

of female sterilization—and Welsh can hardly imagine any doctor lecturing her husband on the joys of fatherhood. “He’d just walk into the doctor’s office and be done in an hour,” she says.

Even if her husband decides to get the snip, Welsh says she still wants her tubes tied, simply because it’s her right. But without a doctor to do it, Welsh’s options are limited. So Welsh, now 34, and her doctor agreed to a compromise: implanting an effective (but less permanent) IUD, until they revisit the topic in five years.

“At that point, I’ll be 39 and a half years old. I don’t know what makes me more sure at 39 than at 34, or 24,” she says. When the time finally rolls around, Welsh plans to insist on the surgery. Does she think that by then, at the tail end of her conventional reproducing years, it is possible her biological clock will kick in? “Absolutely not,” she replies without pause. “I’m as certain on this as I’ve been about anything in my life.”

ROXANNE RICHARD: “Don’t do anything permanent.”

Roxanne Richard, a 38-year-old paramedic living in Ottawa, was married with four children by the age of 22. So when her doctor suggested tubal ligation following the fourth delivery, the surgery seemed like a good option. “When you’ve just had a baby, you’re vulnerable and stressed and tired. You’re not thinking about having another baby,” she says. Richard feels in retrospect that she was pressured by the doctors to have a surgery she didn’t need or even know much about. “I didn’t think it through as much as I should have,” she adds.

Her regret about the procedure kicked in soon after the operation. Just a few months later, when she was comfortably settled into a routine, Richard’s head cleared and she found more time to think. “Your baby starts to get older and you start wondering, ‘Would I do it all again?’ And then you realize, I don’t have that option anymore because it’s been taken away from me. You mourn your body, that feeling of being a woman.”

Richard got divorced in 2004, and a year later she became consumed with baby fever. By then, she was with a new partner, although she says her desire to conceive again was unrelated to their relationship. Two years ago, she scheduled her tubal-reversal surgery. After paying $6,000 (a fee not covered by the provincial government) and going through a painful procedure and a long recovery time, Richard understood that there was still no guarantee she’d be able to conceive. “About six weeks after my surgery, I felt better,” she says. “And I was pregnant.”

To the young women considering tying their tubes, Richard advises they think carefully about other, more easily reversible options: “Take the Pill, do something—but nothing permanent.” Despite all she had to go through, Richard’s story has a happy ending: Her daughter Avery is now 18 months old; Avery’s doting siblings are 16 to 21. And she’s pregnant again—her sixth child is due in December.

THE DOCTOR’S POINT OF VIEW

Every time a patient walks through Vyta Senikas’ door wanting her tubes tied, the OB/GYN has to make a choice. The associate executive VP of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada uses her 25 years of experience to make the call on who is a suitable candidate.

“Typically, women wanting a reversal are 25 to 30 and have one or two children, and they’re asking for it because they have a new partner or their circumstances have changed,” says Senikas. “We have to very carefully explain to patients that, as good as the surgery is, there’s no guarantee a reversal will result in pregnancy.”

But as the science has improved, so have our sensibilities. Senikas remembers a time when tubal ligations required a husband’s signature and were never performed on single women. To decide if the patient was old enough, doctors used a blanket formula: “You took the patient’s age, multiplied it by the number of children she had and added 10. If you got to 100, she got her surgery,” she explains. “I remember thinking to myself, What guy dreamed that up?” Thirty years later, things aren’t so simple, but at least doctors and patients are talking before they tie. An informed discussion with your doctor is the only way to get what you want—and to be sure that you want it.