How Migrants Cross Trump’s U.S.-Mexico Wall

Canadian photographer Isabelle Hayeur has been documenting the growing crisis on America’s southern border

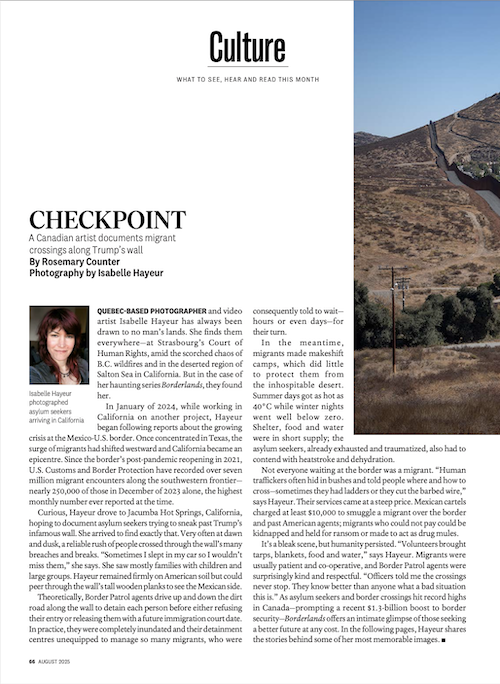

Québécois photographer and video artist Isabelle Hayeur has always been drawn to no man’s lands. She finds them everywhere—at Strasbourg’s Court of Human Rights, amid the scorched chaos of B.C. wildfires and in the deserted region of the Salton Sea in California. But in the case of her haunting series Borderlands, they found her.

In January of 2024, while working in California on another project, Hayeur began following reports about the growing crisis at the Mexico-U.S. border. Once concentrated in Texas, the surge of migrants had shifted westward, and California had become an epicentre. Since the border’s post-pandemic reopening in 2021, U.S. Customs and Border Protection have recorded over seven million migrant encounters along the southwestern frontier. There were nearly 250,000 in December of 2023 alone, the highest monthly number ever reported at the time.

Curious, Hayeur drove to Jacumba Hot Springs, California, hoping to document asylum seekers trying to sneak past Trump’s infamous wall. She arrived to find exactly that. At dawn and dusk, hordes of people would cross through the wall’s many breaches and breaks. “Sometimes I slept in my car so I wouldn’t miss them,” she says. She saw single people, families with children and large groups. Hayeur remained firmly on American soil but could peer through the wall’s tall wooden planks to see the Mexican side.

Theoretically, Border Patrol agents would drive up and down the dirt road along the wall to detain each person before either refusing their entry or releasing them with a future immigration court date. In practice, they were completely inundated. Their detainment centres were unequipped to manage so many migrants, who were consequently told to wait hours or even days for their turn.

In the meantime, migrants made makeshift camps, which did little to protect them from the inhospitable desert. Summer days got as hot as 40°C while winter nights went well below zero. Shelter, food and water were in short supply; the asylum seekers, already exhausted and traumatized, also had to contend with heatstroke and dehydration.

Not everyone waiting at the border was a migrant. “Human traffickers often hid in bushes and told people where and how to cross—sometimes they had ladders or they cut the barbed wire,” says Hayeur. Their services came at a steep price. Mexican cartels charged at least $10,000 to smuggle a migrant over the border and past American agents; migrants who could not pay could be kidnapped and held for ransom or forced to act as drug mules.

It was a bleak scene, but humanity persisted. “Volunteers brought tarps, blankets, food and water,” says Hayeur. Migrants were usually patient and co-operative, and Border Patrol agents were surprisingly kind and respectful. “Officers told me the crossings never stop. They know better than anyone what a bad situation this is.” As asylum seekers and border crossings hit record highs in Canada—prompting a recent $1.3-billion boost to border security—Borderlands offers an intimate glimpse of those seeking a better future at any cost.