Marriage advice and bullet holes

Lessons from my mother, the divorce lawyer

One otherwise normal childhood day, a bullet hole was discovered in our farmhouse’s front window. It was a perfect-dime sized circle through the century-old glass. Since no one was there as a witness, we couldn’t and won’t ever prove a thing.

It could have been a stray, said my mother, still clinging to wishful thinking if you ask me. It could have been there for months or even years; maybe it was from a stone or a marble from the kids next door.

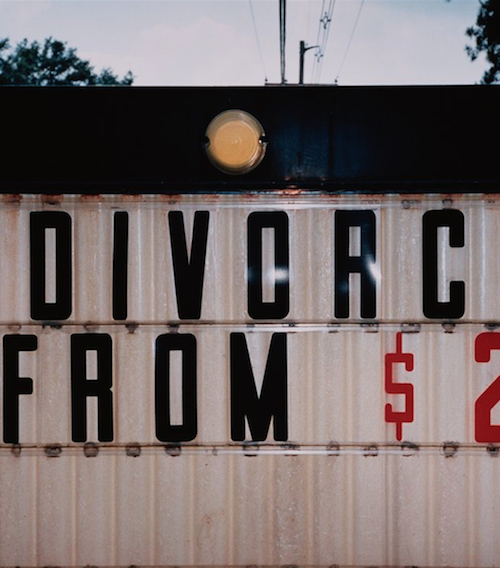

But the whole truth is our turn-of-the-century farmhouse, built by her grandfather, was doing double-duty as a law office. For as long as I can remember, our downstairs library, living and dining room had been converted into my parents’ joint in-home law firm; Dad did criminal defence and Mom practiced family law, specifically divorces.

Guess which one is more dangerous.

The general consensus was that the bullet was retribution from a client’s disgruntled ex-spouse. In a small town like ours, these people weren’t rare. Once when I absent-mindedly dented a (very unforgiving) man’s car in the local bank’s parking lot, I smugly passed him my mother’s card to follow up. “This is my ex-wife’s lawyer,” he said, his face long and white. He never called.

As such, divorce was everywhere at our house. So was free legal advice: “Rosebud,” said my mother only semi-seriously, “every time you walk down the aisle with a man, you need to ask yourself, Is this the man I want my children spending every other weekend with?” Marital advice was equally plentiful. From my wise grandfather, an economics lesson I’ve never forgotten: “Marry for money and you’ll earn every cent.”

But to us, it was all very normal. Hysterical clients routinely called the house at all hours of the night, but we were very happy. Since it would be immediately filled to the brim with domestic dramas, we never had an answering machine, which made staying out past curfew an easy breeze. When my friend’s parents split, as most did over the years, my tween self would help the only way she knew how: “Call my mom,” I’d suggest like a grownup. They always did.

At the same time, and very confusingly, divorce was nowhere at all. Against whatever you might be thinking, my parents had been happily married for years. They still are. We joked that’s because, should they ever split, Mom would take Dad to the cleaners. (They reassured us it would never happen, lest either be given custody of the kids.) Still, I had a recurring dream of my parents’ divorce trial, my three brothers and I called as character witnesses on either side of the unfolding court case. I’m not a child of divorce, per se, but tell my subconscious that.

Nobody in the immediate family divorced – parents, grandparents, siblings, their kids, all are growing up and one by one tying the knot themselves. Yet every engagement is a shock to be wary of, each one met with uncertainty and cynicism and suspicion. All unions are would-be divorces, huge and messy mistakes-in-the-making. Especially mine.

At 32, after six years with my lovely boyfriend, including five of co-habitation and two of home ownership, it was what my dad matter-of-factly called “time to legitimize”. (He and my mother had taken nine years, which I believe is equivalent to 25 in the 1970s, but I digress.) They had discussed, I’m sure, and deemed our union acceptable and advantageous to both parties. After everything and a bullet too, they wanted me to commit to the very institution that I’d spent a whole lifetime watching fail.

I was ripped into two, a part of me on either side of that long-held, semi-true statistic that one in two marriages will end in divorce. To say I had marriage-phobia is a laughable understatement. Reluctant to subscribe to any tradition, I had imagined and designed my own engagement ring, given it to him to give back to me. I did not want any surprises. Yet when he got down on one knee, things felt sudden. I felt distinctly unready. I said yes anyway.

In the next few months, I had mounting anxieties, stomach aches and stress headaches, irrational doubts about the most mundane things. I zoomed in on every detail – an unnecessary shopping spree here, a mouldy cereal bowl there – wondering if this transgression in particular might ultimately prove divorce-worthy in the years to come. My capacity to dwell, of course, to be moody and unforgiving, would kill us just the same and much faster. That we’ll fail and divorce, for some reason as yet unknown, was and is my greatest fear.

There are a million pop culture examples of The One, of love at first sight, of “just knowing”. This kind of blind faith is supposed to trump the rest and plop your marriage on to an elevated plane where you’ll make it for sure. Only it’s not true one bit. Nothing is for sure or forever, and every day is a negotiation. But since it’s far less romantic, we don’t hear those stories much. We aren’t shown the daily grind of couples who have chosen each other, wisely if they’re lucky, who constantly work at themselves and their marriages. For them, love isn’t a vague feeling beyond words but indeed a binding contract to which you both subscribe. I will be here tomorrow, it says.

Of that I have no doubt. And as for the rest, at least at my house, doubt is good. Doubt means you’re looking carefully at the case at hand, that you’re weighing the evidence on all sides. Doubt means you’ve thought long and hard about this. Doubt means you can’t be jinxed, because you’re not that fickle to begin with.

Still I know the odds. I could just as easily become like the hundreds, maybe thousands, of broken-hearted clients that sat sadly in the waiting room (where the bullet came through, though we didn’t advertise that). Or I could be like Mom and Dad, still going to work together every day, and home together every night, holding hands as they discuss their cases.