Roberta Bondar’s dark days sending unlucky moths to their death

The iconic astronaut shares the details of a job that gave her confidence to hold her own in a male-dominated fieldA

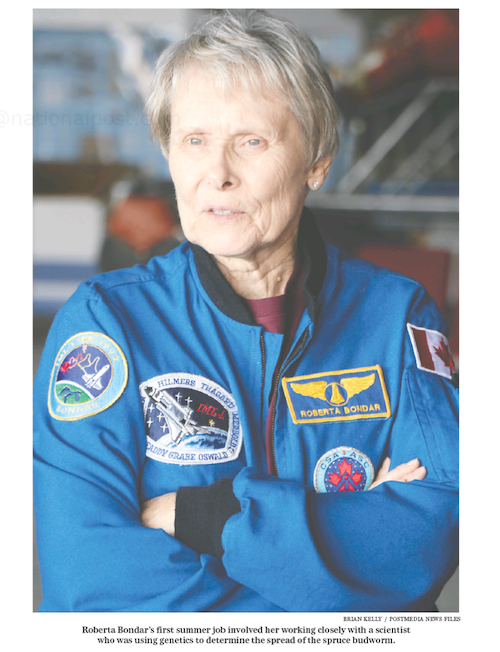

Three decades before Dr. Roberta Bondar became the first Canadian woman to go to space, the then-teenager in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., landed a surprisingly good — and well-paid — gig at a government-funded genetics laboratory. The job itself, however, wasn’t quite so glamorous. In the first instalment of First Hand’s second annual summer job series, the iconic astronaut shares how she spent her summers in a dark basement surrounded by swarms of unlucky moths about to face certain death at her hand. As told to Rosemary Counter.

In 1963, I won an award at a city-wide science fair in Sault Ste. Marie. I’d joined my high-school science club, which only had four members, and we submitted an experiment about DET-resistant flies. I visited the local genetics lab, and while I was there, a federal scientist asked if I would consider a summer job. I put in an application and was accepted.

The first day I walked into the lab, as a grade 12 student, I was so impressed. It was the first time I’d seen scientists in white coats in real life, not just the movies. I’d even get my own white coat, and I’d actually get a new one every Monday. This seemed like a lot at first but it made sense soon. I was usually pretty filthy by Friday.

The ministry kept changing the name of the forestry or fishery lab on us, so we used to call ourselves the Department of Fish & Chips. I didn’t have an official job title either. Maybe I was a “summer helper” at the start and a “research assistant” by the end. The job was well-paid, I thought, and it got better and better, so I ended up working there for six years.

Specifically, I was working closely with a scientist who was using genetics to determine the spread of the spruce budworm, which is officially the choristoneura fumiferana, but I digress. The spruce budworm can be very destructive and they cause infestations all across the country. So we were trying to use genetics to predict their cycles and movement to determine where they’d go next.

But this was way before DNA, so if you wanted to research genetics, you did it in a very old-fashioned way. At the start, that involved clipping the wings off the insects and gluing them down with rubber cement onto microscope slides. Then we could examine the patterns on the wings, which varied dramatically and helped us decide which moths had mated with other moths, all to determine population drift.

Even in the few years I was there, science progressed rapidly. Soon I was promoted and given a new task. I’d take three moths, which were about the size of your fingernail each, and I’d have to euthanize them with ether in a mason jar. When they were, um, freshly laid to rest, I would use a pair of sharp dissecting scissors to cut their heads off. Then I’d dig the eyes out, grind them up, and collect their pigment, which I’d dissolve in different solvents and illuminate in ultraviolet light.

Oh, and I had to do this all in the dark, in a basement that always smelled like mothballs. One time a tarantula got loose in the lab and terrorized us a bit.

Sometimes we got to do field trips, when we’d go deep into the forest to collect bags of fresh balsam buds to deep freeze so that our budworms would have their favourite food all year long. Despite the decapitation stuff, I really liked those little moths. They taught me a real appreciation for insects, and for life and science. I’m still a big insect fan today, except maybe for beetles.

That summer at the lab, I felt like I was really doing something good for humanity. I learned that I could do many good things if I wanted to, and that if I tried I could get good at them too. The job gave me confidence to hold my own in a male-dominated field and it opened my eyes up to what I might do in the world.