Something’s got a hold on me

Pro wrestling has made a comeback at a church basement in Toronto—and everyone’s in on the act

Sunday night at Eastminster United Church is nothing like Sunday morning. Hundreds of devotees gather in the basement of this Toronto house of worship, tall boys and pizza slices in hand, hurling profanities at the stage. “Learn how to wrestle, jackass!” yells one; “Make me, bitch!” the target responds. At this outburst of profanity, the crowd cackles and jeers, “Think of the children!”

The spectators are only half-joking; within this eclectic crowd are indeed young children—including one in a banana costume—alongside grandmothers, young women dressed up like they’re going clubbing, hipsters dressed way down and everyone in between. They’re all superfans of Greektown Wrestling, a grassroots, independent show that began in 2015 in the east end of Toronto.

Tonight’s line-up includes Jock Samson, a redneck Trump supporter; obvious crowd favourite Puf, weighing in at 418 pounds; Sexxxy Eddie, who performs a Magic Mike-worthy striptease down to leopard-print briefs and red bowtie before his fight; Freddy Mercurio, who looks exactly how you’d imagine, only more so; pretty boy R.J. City, who saunters in to Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me”; and Channing Decker, the brains of the whole operation, whose real name is Dave Karkoulas.

“Professionally I’m Channing Decker, but Dave Karkoulas created Greektown Wresting,” he says. With younger brother Jordan, a.k.a. Trent Gibson in the ring, 31-year-old Karkoulas grew up on wrestling “when it was still cool.” He stuck with it through high school, when it distinctly was not. “People had this visceral reaction against wrestling for somehow trying to trick them into believing it was real,” he says of the sport’s golden age in the 1970s and ’80s. “For decades, wrestling’s job was to pretend, and to protect the idea that it was [spontaneous].” Only denying it was staged didn’t work at all: “Then people get their backs up, like ‘I’m far too smart for that!’ ”

Somehow between then and now, the public’s understanding of wrestling changed—mostly. “Certainly some still view it like some kind of trailer park soap opera,” says Jordan Karkoulas, “but I promise you those people have never been to a live show. Would you go see Cirque du Soleil and say, ‘Oh, that’s so fake?’ ” Carefully curated personas are part of the job and not easy, explains Detroit-based wrestler Allysin Kay, or Sienna, a Greektown regular. “We put a ton of thought into our characters and performances,” she says. “Then it’s like a live movie and we get one take.”

Television shows like Netflix’s GLOW are letting mainstream viewers peek backstage to better understand the sport. Rather than campy combat, they see performance art, a hotly contested phrase in wrestling that the elder Karkoulas brother feels is apt. Tonight, Channing and Franky the Beast King, a ghoulish villain in a fur-trimmed cape that the Game of Thrones hero Jon Snow might wear, spend half their round fighting outside the ring and amongst the audience (“Back up, guys, back up!” instructs the ref, like a stage manager). “I consider myself an athlete, actor and performer,” Karkoulas says. At a live show with cheers and boos, he adds, you could easily argue you’re enjoying interactive performance art.

Either way, it’s a welcome surprise to most who walk off Danforth Avenue through Greektown’s doors. Some 500 fans can squeeze into the church basement, where the troupe began staging its matches after outgrowing a series of legion halls.

One unlikely fan is John Williamson, a 28-year-old café manager who’d never watched wrestling. He first came to Greektown Wrestling like many others: reluctantly, on the arm of a friend. “What surprised me most was the crowd,” he says. “Everyone was just so into it that it’s hard not to get into it too.” That was two years ago and, despite his initial take on the spectacle as “contrived and silly,” he hasn’t missed a show since.

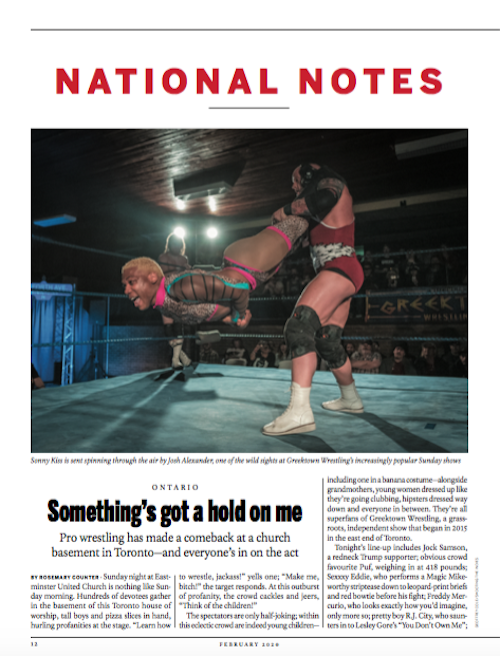

Wrestling might be the last thing you’d expect to circle back into vogue, admits Dave Karkoulas; but “if you follow the money, it’s happening.” Last year saw a billion-dollar investment in All Elite Wrestling, the first challenger to the WWE in two decades. Prime time exposure, however, is merely the most visible piece of the boom: independent wrestlers like those on Greektown’s stage are building their fan bases through the reach of social media. Technology makes it easy for amateurs to record, edit and stream their performances on Facebook or YouTube. It also allows unconventional fan favourites, like Sonny Kiss, a gender-bending LGBTQ advocate who wows with backflips and splits, to find their audiences and go professional; the Greektown star signed with All Elite last February.

“I like to think wrestling is the same, but the audience has changed,” says Dave Karkoulas. Members of this crowd, for instance, laugh alongside performers, participate when they can and don’t take any of it terribly seriously. Like retro TV shows getting reboots, wrestling seems to benefit from nostalgia for simpler times. “People see the news and watch politics and suddenly there’s a place and need for this carefree entertainment,” says Karkoulas. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s a really great time to be a wrestler.”