The Apartments That Inspired Only Murders in the Building

The Ansonia is the real-life apartment complex that’s been home to murder, mayhem, and a swingers club.

Sure, Martin Short, Steve Martin, and Selena Gomez may be top-billed. But there’s only one true, titular star of Hulu’s comedy-crime-whodunit Only Murders in the Building.

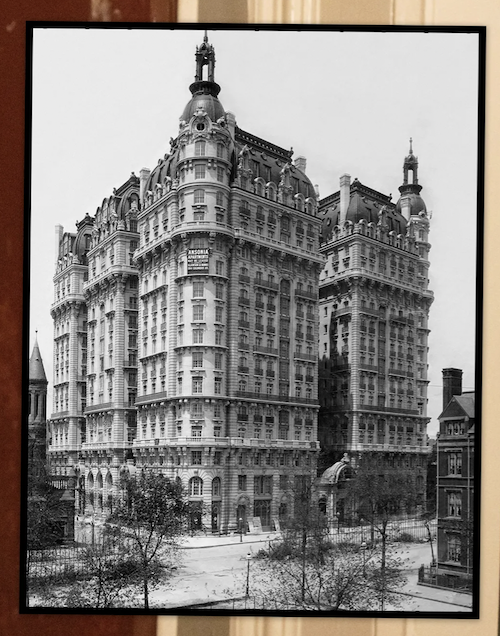

Officially, the crime-solving podcasters’ Upper West Side residence is the Arconia, filmed using a cobbled mix of the Belnord’s facade, interior sets with statement wallpaper galore in the Bronx, and countless outdoor locations in and around the city. Though the Belnord tends usually hog attention from fans, the Arconia’s name and colorful residents seem much more closely linked to the Ansonia, the legendary real-life luxury apartment building that occupies a full city block on Broadway between 73rd and 74th Street.

Made up of 17 stories and around 400 unique units, the building is every New Yorker’s real-estate dream come true: Parisian-inspired with Juliet balconies, round turrets with gray terracotta details, and an opulent archway entry. Inside are hardwood herringbone floors, floor-to-ceiling windows, and a sweeping marbled staircase spiraling beneath a grand domed skylight. Today, a 3,000-plus square foot, four-bedroom, three-bathroom unit in the building is listed for almost $9,000,000.

For that asking price you don’t just get luxurious modern living—you also get the Ansonia’s bawdy history and raucous reputation, which includes everything from a swingers club to gruesome murders fit for binge-worthy TV. Here are just some of the secrets from the Ansonia’s infamous wild heyday.

Its multimillionaire founder apparently had a dodgy romantic past. This season in episode two, Only Murders flashes back for a quick history lesson. Their mustached architect is an “infamous playboy” whose secret lift leads to peepholes to spy on ladies dressing. His real-life counterpart may have been sketchy in other ways. Born-and-bred New Yorker William Earl Dodge Stokes, with a million dollars in his pocket having sued his own brother after their father died, turned away from the family mining business and toward real estate and development on the Upper West Side, a poor pocket of boarding houses and boozy taverns at that point in the late 1800s.

But it was the other, swankier side of the city where Stokes spotted a photo in a shop window of 15-year-old heiress Rita Hernandez de Alba de Acosta and decided she’d be his teenage bride. He was 42 and said to be very fond of young, newly pubescent, girls. It’s thought that Rita reluctantly married him for money, produced a single male heir, and walked away around age 21 with what was rumored to be the largest divorce settlement on record at the time—$2 million in cash and $36,000 annually in alimony, allegedly.

Stokes scooped the land from impoverished orphans: Stokes may have fallen in love with a child, but it wasn’t enough to dissuade him from purchasing and developing land that was previously part of the New York Orphan Asylum. Stokes envisioned the dirt road as Broadway, paved and orphan-free, a glamorous boulevard of shops and services for well-dressed pedestrians. There, he would build the “grandest hotel in Manhattan”—way better than measly nine stories of the recently completed Dakota down the street—with every over-the-top amenity he could imagine: the world’s largest indoor pool, restaurants decorated in the style of Louis XIV, Turkish baths, and a large fountain housing live seals. When it officially opened in 1904, the Ansonia also had a ballroom, bank, barbershop, and tailor on-site.

The Ansonia had a surprisingly large number of nonhuman inhabitants: The fountain seals were just one species of animal that Stokes moved into the Ansonia, which he fancied as something of a self-sustaining Utopia. Stokes resided with four geese and a pig as personal pets, while the other animals were delegated to the roof: ducks, 500 chickens (fresh eggs were delivered daily to tenants), six goats, and a (small) bear. The Department of Health stepped in to stop his so-called “farm in the sky” in 1907, but Stokes continued to hide illegal animals in the hotel. When his second young wife, Helen, divorced Stokes in the early 1920s, she was sure to tell the judge that her ex had 47 chickens waddling around their lavish abode.

It was home base for the Black Sox Scandal: Many athletes over the years made the Ansonia their home, including Babe Ruth and boxer Jack Dempsey, but whatever shenanigans they inevitably got up to cannot compare to that of Chick Gandil. Gandil, the Chicago White Sox first baseman, gathered at the Ansonia along with the team’s pitcher to meet with an ex-player representing gambling king Arnold “The Big Bankroll” Rothstein. For at least $10,000 each, they agreed to throw the World Series against Cincinnati in what would become the biggest baseball scandal in history.

The hotel became a hangout for criminal kingpins: Unsavory characters were welcomed guests at the Ansonia. After the hotel officially opened in April 1904, Stokes is said to have encouraged racketeer Al Adams, a.k.a. “The Policy King” or “Meanest Man in New York,” to move right from his cell at Sing Sing into the Ansonia. After a two-year stay, Adams was found dead by a bullet in Suite 1579. The coroner eventually declared the death a suicide, though initially, he claimed that Adams was actually murdered—by Stokes, no less, over an unpaid debt.

One of Stokes’s mistresses tried to kill the hotel magnate: Stokes only maybe shot Adams, but he definitely was shot by his 22-year-old mistress, Lillian Graham. The vaudeville showgirl had his risqué love letters in hand; she said he attacked her when she refused to return them while he said she was enraged he wouldn’t pay $25,000 in blackmail. Either way, Stokes was shot three times in the legs, but survived.

The Ansonia declined into disrepair and was sold at a bankruptcy auction: Stokes died an old man of pneumonia and the hotel passed to his son, who had little interest in his father’s hotel. The junior Stokes sold it to a crooked landlord, whose financial mismanagement led to bankruptcy. The landlord went to prison while the Ansonia went to auction; it was scooped up by a local sign maker named Jacob Starr for a mere $50,000. He allowed the Ansonia to further decline, later actually recommending it be demolished, but not before he made a few bucks.

There was a gay bathhouse in the basement: In the swinging ’60s, Starr leased Ansonia’s once-famous, long-abandoned swimming pool (plus Turkish baths) to Steve Ostrow, who turned the spot into a cabaret slash sex clubs called the Continental Baths. With a waterfall, orgy room, and a K-Y jelly dispenser, visitors could be voyeurs to sex acts while simultaneously catching a Broadway-caliber show. Performers included Barry Manilow and Bette Midler, who rose to fame as “Bathhouse Betty.”

Last but not least, the Ansonia gets a swingers club: In 1977, the baths closed and Plato’s Retreat opened. Considered one of the world’s most infamous sex clubs, the “members only” spot added mattresses on the floor, a 50-plus-person Jacuzzi, “clothing optional” disco dancing, an open bar and full buffet, and…a backgammon lounge.