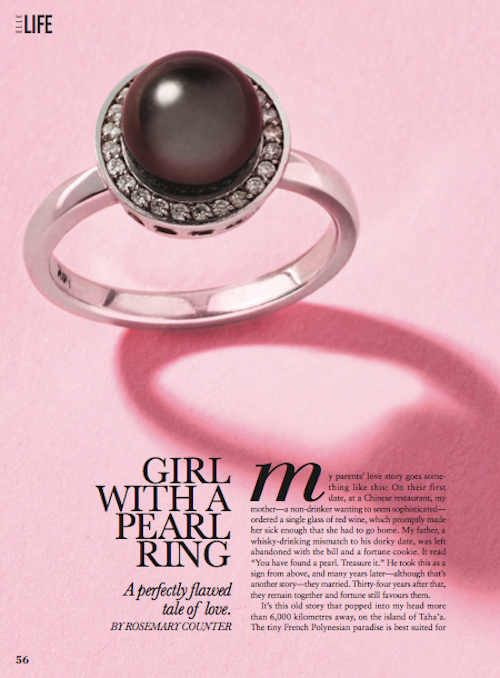

Girl with a Pearl Ring

A perfectly flawed tale of love

My parents’ love story goes something like this: On their first date, at a Chinese restaurant, my mother—a non-drinker wanting to seem sophisticated— ordered a single glass of red wine, which promptly made her sick enough that she had to go home. My father, a whisky-drinking mismatch to his dorky date, was left abandoned with the bill and a fortune cookie. It read “You have found a pearl. Treasure it.” He took this as a sign from above, and many years later—although that’s another story—they married. Thirty-four years after that, still together, fortune still favours them.

It’s this old story that popped into my head more than 6,000 kilometres away, on the island of Taha’a. The tiny French Polynesian paradise is best suited for lovers, but I was there without my boyfriend to tour local pearl farms. I was looking at black pearls—the meticulous work of the Pinctada margaritifera, the rare black-lipped oyster that lives only in the warm turquoise waters around French Polynesia—and absorbing all the luscious lore that comes with them. The Chinese believed they grew in the eyes of dragons; the Japanese said all pearls were born from the tears of mermaids.

The odds of finding a natural freshwater pearl are about one in 10,000, and black ones are even rarer than that. But the odds at the Tahitian pearl farms aren’t particularly encouraging either. It takes five years for an oyster to grow a pearl, diligently adding concentric layer upon layer of calcium carbonate. But even after pearls mature and end up on a necklace or a ring, they mustn’t be locked away in a jewellery box indefinitely. Because they have a 3-percent water content, they need moisture, such as skin contact, to stay “alive”; without it, they become dull and “die.” Quality pearls are about 1 in 100, which is probably right around the ratio of good to bad dates I’ve had.

Some of the pearls, like some of the men I’ve gone out with, lacked lustre, some had superficial imperfections, some were dead inside. Some were gorgeous but not quite my style, some I was drawn to immediately, others grew on me after a while. But, finally, one pearl—like the perfect man—stood out: a shining little black sphere, seven millimetres across, that had subtle hints of pinks and blues and was iridescent in the sunlight in the palm of my hand.

Then I started to think about love and about the past five years that I’d spent with my guy. And then I started to think about how special it is to have someone loving you from the other side of the world. Then a new romantic fantasy popped into my head: “What if I bought this pearl, set it in a white-gold ring and then gave it to him to give to me?” I never wanted an engagement ring—and I couldn’t see myself wearing a diamond—but there was something about this pearl that seduced me.

Orchestrating my own proposal was a risky and perhaps crazy move—not just for all the obvious reasons, like rejection and restraining orders, but because I was planning to do it with a black pearl, which is said to bring bad luck. This is because a pearl is born of a flaw of nature: It starts as a piece of sand or shell trapped inside an oyster, foreign and painful, and builds up over time. An old wives’ tale warns that a bride who wears pearls on her wedding day will shed a tear for every single one. And to buy and wear your own pearls, says another, is particularly unwise—unless it’s your birthstone. And since I was born in June, it is mine. Just in case.

So, for a bargain of $250, I bought the pearl. Back at the resort, I proudly displayed my impromptu purchase to the woman at the pearl boutique. She took one look through a magnifying glass and spotted a blemish. I hadn’t noticed it before, and I was visibly disappointed. I wanted a perfect pearl like a perfect husband—one I could bring to cocktail parties and show off and brag about to my friends. A pearl that would be exactly what I wanted it to be already. A pearl that would take the garbage out without being asked.

But neither a man nor a pearl is perfect, she said, nor would I want them to be. “A pearl without a flaw is a fake pearl,” she said. “Just like humans—if we were all the same, it would be a nightmare.” But could I wear this pearl, day in and day out, with every mood and ensem- ble? Could I care for it delicately and consistently so that it still glows in five years? Ten? Thirty-four?

I could try, that’s for sure. I could work at it bit by bit and build something beautiful. I started the week I got back to Toronto: I casually mentioned to my boyfriend that I had bought a pearl and was up to something special. Then, a couple of months later, I got bolder. “This woman is expecting your call,” I mumbled nervously, handing him Toronto-based ring designer Megan Dunn’s pencil sketch and business card. “Is this the kind of ring I think it is?” he asked. We’d discussed marriage before but never so concretely. “It can be whatever we want it to be,” I explained.

He tucked the card into his pocket, equal parts surprised and impressed. He then let me linger in torturous suspense for six long months. (I broke just once and asked if he’d gifted my ring elsewhere, but I was told to be patient.) Then, just when I’d almost forgotten, at dusk on his favourite hill at his family’s farm, he finally got down on one knee. Turns out he had a proposal fantasy too.

Although I don’t particularly believe in omens, I can only hope that my Tahitian black pearl brings a lifetime of good luck and love. To me, a non-believer in dragons and mermaids, a pearl is a metaphor for how something can grow, through time and effort, into something spectacular. This, I hope, will be part of the love story I share with our kids, if we have any. I won’t tell them I proposed to myself; I will say I gently pried him open and carefully planted the seed.