The wolf of Juan de Fuca

A hot ticket among the outdoor set, Victoria’s lupine ‘rock star’ may be too popular for his own good

On a crisp Sunday morning last month, 50 birdwatchers boarded a tranquil tour of Victoria’s Oak Bay. As the boat cruised through the islands, a two-km-wide cluster known as the Songhees or Chatham Islands, the guide began his usual tale of local lore: “Five years ago, stories began about a wolf on the island. People in the city could hear him howling at night.” Sightings were infrequent, usually disregarded as a lost large dog, and even a er countless tours, guide Brett Soberg had spotted the creature in the distance only twice. “Literally seconds later, he meandered out of the bush and sat right down,” he says. Needless to say, nobody cared anymore about birds.

On board was Nancy Brown-Schembri, an amateur wildlife photographer expecting to snap some sea birds and, if lucky, a whale. “Suddenly someone called out, ‘I see the wolf!’ Everyone rushed to the side of the boat and we all just silently looked up.” For 10 minutes, looking comfortable and con dent, there he sat: the little-seen, much-hyped lone wolf said to have swum the kilometre-wide channel to make the islands his home. Brown-Schembri’s photographs were plastered across the nightly news.

Coastal (or sea) wolves are the same species as the North American grey wolf, but ecologically and genetically distinct, says Chris Darimont, wolf expert and University of Victoria geography professor. “They’re smaller, they eat mostly seafood and they swim a bit better.” Their range once stretched from southeast Alaska to northern Mexico; nowadays, about 100 km north of Vancouver is as far down the continent as most roam, making this wolf ’s island home exceedingly rare. “He dispersed from his family group and took some wrong turns,” says Darimont. “Instead of finding a place with abundant prey and few people, he somehow wound his way through the suburbs of Victoria, through parks and backyards. Then I imagine he saw a patch of green on the horizon and swam for it.”

But this is only the scientific version of this story; a spiritual one is equally alluring. In July 2012, Songhees Nation Chief Robert Sam—an outspoken champion of Aboriginal rights and advocate of preserving the islands, which are currently part reserve land and part B.C. Provincial Park—suddenly died. That fall, the wolf appeared. “The new chief went on television and spoke at length of the community’s desire to leave the wolf alone,” recalls Mark Salter, Songhees Nation tourism manager. The 700 Songhees people probably have 700 different opinions, he adds, but “portions of the com- munity identify as part of the wolf clan, and there are members who find solace in the fact that he’s returned in the spirit of the wolf to protect the island.” While there’s been ongoing talk of trapping and removing the wolf, the Songhees flatly reject the option.

If this all feels familiar, recall Luna the orca. In the early 2000s, the young whale was separated from its family and spent five years off Vancouver Island’s coast, drawing tourists and getting all too comfortable with humans. Government efforts to capture and move Luna were met with opposition from the Mowachaht-Muchalaht Nation, whose recently deceased chief had said his spirit would return as a whale. The parties never reached a resolution, and in 2006 Luna was struck and killed by a boat.

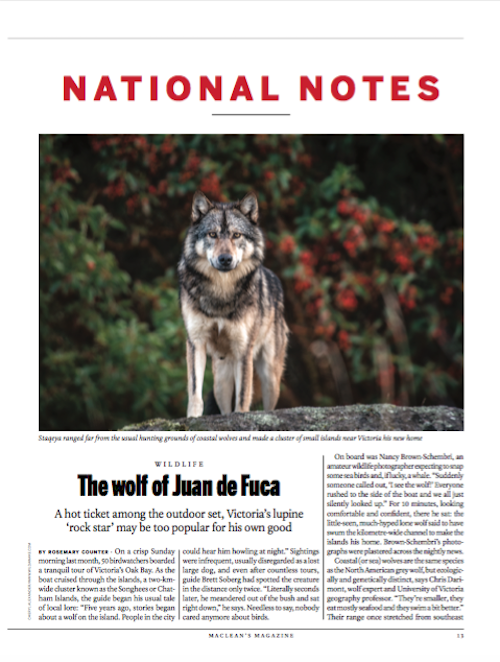

Parallels between Luna and the handsome animal the Songhees have named Staqeya (“wolf ” in Lekwungen) will inevitably be drawn, but there are also important distinctions. Namely: the beast is thriving, eating mostly seals, and lots of them. “I must say, he looks really good,” says Darimont, citing Staqeya’s healthy frame and thick coat. He swims freely between the islands, has shown no aggression and rarely interacts with people.

One incident last fall, however, made headlines. A visiting family with children—who Salter notes “illegally brought their dog and were trespassing on Songhees land”—found themselves being followed by Staqeya. They retreated to the lighthouse, made a distress call and were rescued by a patrol officer who came ashore with a gun.” The close call led B.C. Parks to close the park until spring while the situation is assessed. Locals disagree about the legality of who is allowed on the beach, but Salter is clear: “These islands are the Songhees Nation’s and there’s absolutely no access right now, at all.”

But with a wolf to be seen just a 10-minute boat ride away, many find the islands irresistible. Cheryl Alexander, an environmental consultant turned photographer from Victoria, has been visiting in her canoe for 40 years. “I didn’t seek out the wolf,” she says, “it seemed to seek me out.” Alexander had already read about the wolf in the paper and heard him howl when, at dusk in spring 2014, movement in the water caught her eye. “He just came out of the water and walked up the beach, disappearing into the bush. That was it; I was captivated.”

Alexander visited a few times a week after that—with special permission from the Songhees—and learned his patterns and behaviours. She might see him four times in a week or not at all, and has taken thousands of photographs from as close as three metres, which is close enough. “I’ve never once felt fearful, and in some ways touching him would be wonderful, but I rationally know I shouldn’t and won’t. He’s a wild animal.”

Until the incident with the dog last fall, Alexander thought it best to keep quiet about the wolf. “I’ve since changed my mind and think people need to know he’s there, that he’s very special and that we need to protect him.” At about seven years old, Staqeya could live about seven more, his would-be protectors point out, and lots of space with less human interaction would be best. “It’d be great if he’d garner less attention,” says Salter, “but it’s not easy when he likes to show off like a rock star.”