Helping moose get it on

A ‘moose-sex corridor’ between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia is helping lonely ruminants find love

The Chignecto Isthmus—the corridor connecting New Brunswick to Nova Scotia that at its narrowest is just 24 km wide—poses a uniquely Canadian problem. On one side of the land bridge thrives a healthy population of more than 25,000 moose; on the other, numbers have dwindled to as few as 500. Long classified as endangered, the Nova Scotia moose is perilously close to extinction.

All moose face poaching, parasites, climate change and habitat loss. But unlike their neighbours, Nova Scotia moose were dealt an unlucky geographical hand. “Any animal moving in or out has to pass through the isthmus, the geographical formation between the Bay of Fundy and the Northumberland Strait,” explains Paula Noel, New Brunswick program manager at the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC). But the corridor is increasingly a pinch-point for travelling wildlife: if the expansion of roadways and housing developments in the area continues, says Noel, “we’re going to have problems.”

In that event, she warns, Nova Scotia will become “almost an island, with less wildlife diversity and genetic variation.” This presents a larger problem: “Isolation is a big deal,” says Joe Nocera, assistant professor of wildlife ecology at the University of New Brunswick. “There’s not enough connectivity between populations and zero potential to share genes.” Inbred moose, for example, have lower-than-normal birth rates and body masses, leading to further decline in populations.

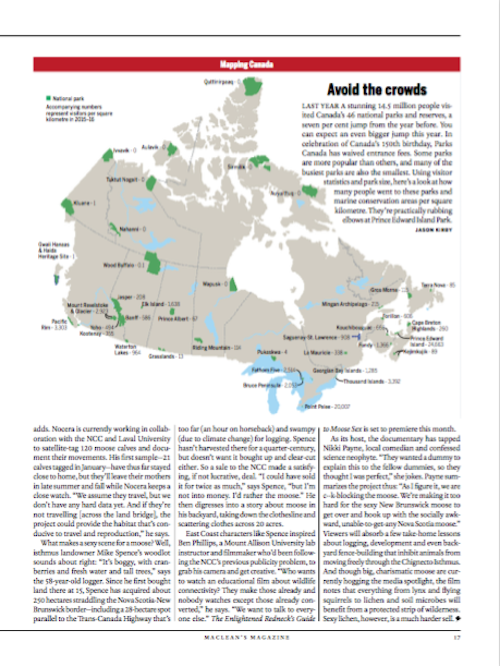

This spring, the NCC procured three new properties totalling 95 hectares as part of an ongoing campaign to create a haven of protected forests and wetlands on the isthmus. Their running total now stands at more than 1,200 hectares. Yet from the outset, their e orts seemed plagued by mixed messages. Even now, for example, you can hunt moose on the New Brunswick side of the isthmus, but not in Nova Scotia. How, then, can they impress the urgency of the situation on the public?

The answer lay not in science, but in branding. Cheeky NCC office workers had dubbed the narrow strip, officially necessary for genetic variability, the “moose-sex corridor”—an inside joke that stuck. Though already a few years old, the clever moniker garnered unforeseen national attention. “Moose getting their own corridor of land for sex,” said the Toronto Star, while Halifax’s Chronicle-Herald encouraged readers donate to “help moose have more sex at Christmas.” Such silliness is all just fine by the NCC. “We know when we start talking like I am, like a biologist, people tune out,” says Noel. “They want to hear about the sex.”

That said, actual moose sex is “not particularly romantic,” says Nocera. “They do it like most ungulates do, which is the male goes into hormonal overdrive during rutting season and finds a receptive female. That’s pretty much the end of the male’s role,” he adds. Nocera is currently working in collaboration with the NCC and Laval University to satellite-tag 120 moose calves and document their movements. His first sample—21 calves tagged in January—have thus far stayed close to home, but they’ll leave their mothers in late summer and fall while Nocera keeps a close watch. “We assume they travel, but we don’t have any hard data yet. And if they’re not travelling [across the land bridge], the project could provide the habitat that’s conducive to travel and reproduction,” he says.

What makes a sexy scene for a moose? Well, isthmus landowner Mike Spence’s woodlot sounds about right: “It’s boggy, with cranberries and fresh water and tall trees,” says the 58-year-old logger. Since he first bought land there at 15, Spence has acquired about 250 hectares straddling the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick border—including a 28-hectare spot parallel to the Trans-Canada Highway that’s too far (an hour on horseback) and swampy (due to climate change) for logging. Spence hasn’t harvested there for a quarter-century, but doesn’t want it bought up and clear-cut either. So a sale to the NCC made a satisfying, if not lucrative, deal. “I could have sold it for twice as much,” says Spence, “but I’m not into money. I’d rather the moose.” He then digresses into a story about moose in his backyard, taking down the clothesline and scattering clothes across 20 acres.

East Coast characters like Spence inspired Ben Phillips, a Mount Allison University lab instructor and filmmaker who’d been following the NCC’s previous publicity problem, to grab his camera and get creative. “Who wants to watch an educational film about wildlife connectivity? They make those already and nobody watches except those already converted,” he says. “We want to talk to everyone else.” The Enlightened Redneck’s Guide to Moose Sex is set to premiere this month.

As its host, the documentary has tapped Nikki Payne, local comedian and confessed science neophyte. “They wanted a dummy to explain this to the fellow dummies, so they thought I was perfect,” she jokes. Payne summarizes the project thus: “As I figure it, we are cock-blocking the moose. We’re making it too hard for the sexy New Brunswick moose to get over and hook up with the socially awk- ward, unable-to-get-any Nova Scotia moose.”

Viewers will absorb a few take-home lessons about logging, development and even backyard fence-building that inhibit animals from moving freely through the Chignecto Isthmus. And though big, charismatic moose are currently hogging the media spotlight, the film notes that everything from lynx and flying squirrels to lichen and soil microbes will benefit from a protected strip of wilderness. Sexy lichen, however, is a much harder sell.