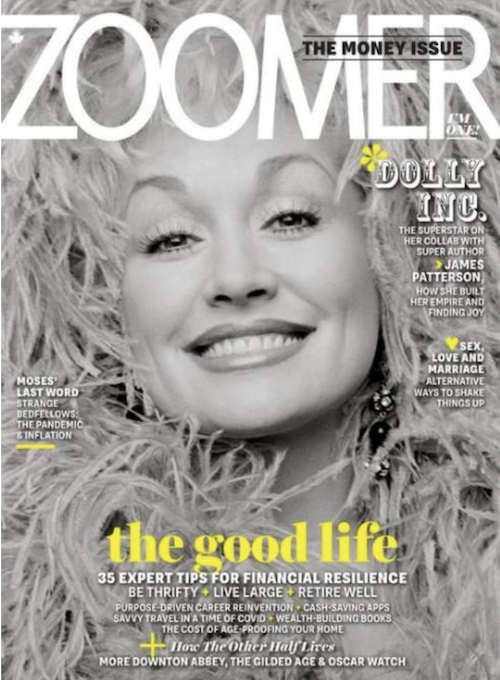

Welcome to the Dollyverse

The country star teams up with literary star James Patterson on Run, Rose, Run, and ends up inventing a new genre of musical novel

An old television clip recently made new rounds on social media. Barbara Walters, having just “made it” as on-air talent in the old boys’ club of broadcast journalism in 1977, is perched on one stiff leather couch opposite Dolly Parton. Tresses teased tall and an oversized blue rose tucked behind her ear, she is being bombarded by questions, with undertones varying from condescension to disdain. “Dolly, did you look like this when you were a kid? Is it ‘all you’? Do you ever feel that you’re a joke?”

Even if she would have rather sucker-punched Walters, Parton — the Nashville, Tenn., singer-songwriter then on the cusp of superstardom — smiles sweetly and answers with grace. “It’s certainly a choice,” she begins, before dealing out a trademark Dollyism. “I would never stoop so low as to be fashionable.” And then, as if she could see the future in a crystal ball, she delivers a telling take in her soft Southern drawl. “All of these years, people have thought the joke was on me, but it’s actually been on the public. I know exactly what I’m doing, and I can change at any time.”

And she has transformed: from country queen to pop star, singer to actress, business tycoon to philanthropist. Still rocking big hair and big boobs, she’s also exactly the same — thanks to impeccable makeup atop a wrinkle-free face — as if she’s kicked up her six-inch stilettos and waited patiently for the world to embrace her trademark, country-glam look and laud her third-wave feminism, business acumen and big heart.

All I know for sure is that, when the world went to hell in 2020, Parton emerged as an unlikely hero. While the pandemic turned most people’s lives upside down, she promised light at the end of the tunnel with a US$1-million donation to Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s COVID-19 research fund, which proved critical in the early stages of the Moderna vaccine’s development. The day she received her first shot in May 2021, she wrote a viral take on her 1973 hit “Jolene” to raise awareness. “Vaccine, vaccine, vaccine, vacciiiinnne,” she sang. “I’m begging of you, please don’t hesitate.”

If there were one earthly being we could all rally around, it might be Parton, who after a half-century in the spotlight has proven to be all things to all people: gay icon, good Christian, third-wave feminist and Black ally. In 1997, she sparked the revitalization of a historically Black Nashville neighbourhood when she used royalties from her songwriting credit on Whitney Houston’s version of “I Will Always Love You” to buy a commercial complex in 12 South for her office. In 2020, just months after George Floyd was murdered by a police officer, Parton did not mince words when she told Billboard magazine: “Of course Black Lives Matter. Do we think our little white asses are the only ones that matter?”

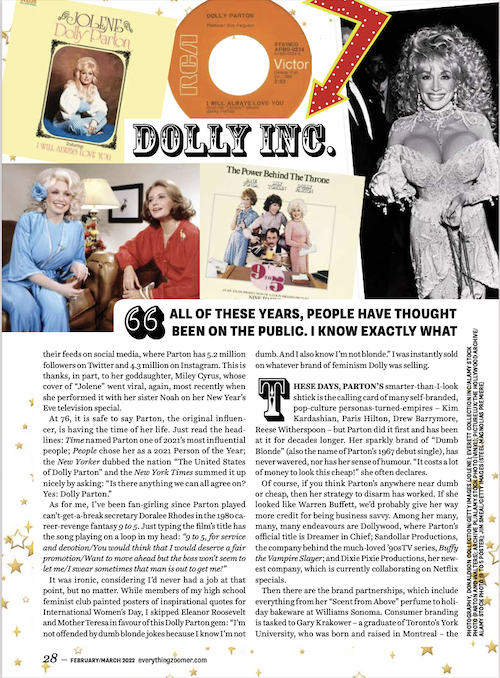

One of America’s richest self-made women, she is loved by grandmas who tune into her songs on the radio and younger generations who discover her by refreshing their feeds on social media, where Parton has 5.2 million followers on Twitter and 4.3 million on Instagram. This is thanks, in part, to her goddaughter, Miley Cyrus, whose cover of “Jolene” went viral, again, most recently when she performed it with her sister Noah on her New Year’s Eve television special.

At 76, it is safe to say Parton, the original influencer, is having the time of her life. Just read the headlines: Time named Parton one of 2021’s most influential people; People chose her as a 2021 Person of the Year; the New Yorker dubbed the nation “The United States of Dolly Parton” and the New York Times summed it up nicely by asking: “Is there anything we can all agree on? Yes: Dolly Parton.”

As for me, I’ve been fan-girling since Parton played can’t-get-a-break secretary Doralee Rhodes in the 1980 career-revenge fantasy 9 to 5. Just typing the film’s title has the song playing on a loop in my head: “9 to 5, for service and devotion/You would think that I would deserve a fair promotion/Want to move ahead but the boss won’t seem to let me/I swear sometimes that man is out to get me!”

It was ironic, considering I’d never had a job at that point, but no matter. While members of my high school feminist club painted posters of inspirational quotes for International Women’s Day, I skipped Eleanor Roosevelt and Mother Teresa in favour of this Dolly Parton gem: “I’m not offended by dumb blonde jokes because I know I’m not dumb. And I also know I’m not blonde.” I was instantly sold on whatever brand of feminism Dolly was selling.

These days, Parton’s smarter-than-I-look shtick is the calling card of many self-branded, pop-culture personas-turned-empires — Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, Drew Barrymore, Reese Witherspoon — but Parton did it first and has been at it for decades longer. Her sparkly brand of “Dumb Blonde” (also the name of Parton’s 1967 debut single), has never wavered, nor has her sense of humour. “It costs a lot of money to look this cheap!” she often declares.

Of course, if you think Parton’s anywhere near dumb or cheap, then her strategy to disarm has worked. If she looked like Warren Buffett, we’d probably give her way more credit for being business savvy. Among her many, many, many endeavours are Dollywood, where Parton’s official title is Dreamer in Chief; Sandollar Productions, the company behind the much-loved ’90s TV series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer; and Dixie Pixie Productions, her newest company, which is currently collaborating on Netflix specials.

Then there are the brand partnerships, which include everything from her “Scent from Above” perfume to holiday bakeware at Williams Sonoma. Consumer branding is tasked to Gary Krakower — a graduate of Toronto’s York University, who was born and raised in Montreal — the vice-president of licensing for IMG, a New York-based global events and talent-management company. His first meeting with Parton was unforgettable.

“She mentioned that she really loved red shoes,” recalls Krakower. “She said, ‘I can’t express it, but I can sing it,’ and then, off the top of her head, she sang a two-minute song about red shoes.” So can we expect Dolly-brand red pumps any time soon? “Stay tuned,” he teases.

Naturally, Parton is very, very busy, starting many days at 4 a.m., when she meets with her team to tackle a daily “ask Dolly” to-do list. Her manager has said they turn down 90 per cent of requests for her time, with the winners offering “minimal Dolly time and maximum exposure.” It makes me absolutely giddy that I’ve made the cut. And very nervous.

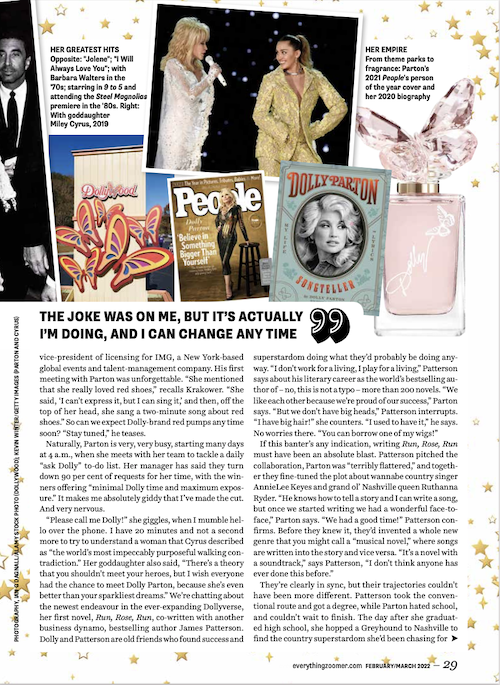

“Please call me Dolly!” she giggles, when I mumble hello over the phone. I have 20 minutes and not a second more to try to understand a woman that Cyrus described as “the world’s most impeccably purposeful walking contradiction.” Her goddaughter also said, “There’s a theory that you shouldn’t meet your heroes, but I wish everyone had the chance to meet Dolly Parton, because she’s even better than your sparkliest dreams.” We’re chatting about the newest endeavour in the ever-expanding Dollyverse, her first novel, Run, Rose, Run, co-written with another business dynamo, bestselling author James Patterson. Dolly and Patterson are old friends who found success and superstardom doing what they’d probably be doing anyway. “I don’t work for a living, I play for a living,” Patterson says about his literary career as the world’s bestselling author of — no, this is not a typo — more than 200 novels. “We like each other because we’re proud of our success,” Parton says. “But we don’t have big heads,” Patterson interrupts. “I have big hair!” she counters. “I used to have it,” he says. No worries there. “You can borrow one of my wigs!”

If this banter’s any indication, writing Run, Rose, Run must have been an absolute blast. Patterson pitched the collaboration, Parton was “terribly flattered,” and together they fine-tuned the plot about wannabe country singer AnnieLee Keyes and grand ol’ Nashville queen Ruthanna Ryder. “He knows how to tell a story and I can write a song, but once we started writing we had a wonderful face-to-face,” Parton says. “We had a good time!” Patterson confirms. Before they knew it, they’d invented a whole new genre that you might call a “musical novel,” where songs are written into the story and vice versa. “It’s a novel with a soundtrack,” says Patterson, “I don’t think anyone has ever done this before.”

They’re clearly in sync, but their trajectories couldn’t have been more different. Patterson took the conventional route and got a degree, while Parton hated school, and couldn’t wait to finish. The day after she graduated high school, she hopped a Greyhound to Nashville to find the country superstardom she’d been chasing for as long as she could remember. (It’s where Dolly met Carl Dean, her husband of 55 years, at the Wishy-Washy Laundromat.) By then, the seeds had been planted for Parton’s over-the-top, hyper-femme signature style. An ample-bosomed early bloomer, who was bullied for her (undeserved) bad reputation, Parton subverted the gossip mill by beating everyone else to the punchline. Eschewing prim and proper late-’50s fashions, she famously said she modelled her outrageous look on the “town tramp” (said lovingly, with admiration), spending her humble paycheques from radio jobs on short skirts, high heels, lipstick and peroxide.

Parton’s glam-up was noticed by country star Porter Wagoner, who offered her a gig as musical sidekick on his syndicated weekly TV show at a starting salary of US$60,000 a year. Though the pay was well beyond her wildest dreams, Parton acted cool and told him she’d think about it. So began a legendary seven-year partnership Parton likened to a marriage, a “love-hate relationship, all mangled up with business.”

If Wagoner wanted a pretty little work wife to stay in his shadow, he chose poorly. When her first music contract with Monument Records expired, she co-founded the Owe-Par Publishing Company with her musically minded Uncle Bill. Parton retained a controlling interest — 51 per cent to Bill’s 49 — in her songs, which, much to Wagoner’s chagrin, increasingly outsold his. As her star power grew, Wagoner became increasingly jealous, competitive and possessive.

While her country contemporaries preached “Stand By Your Man,” Parton decided to stand on her own, leaving Wagoner in what the press dubbed a “hillbilly divorce.” He didn’t make it easy, later suing her for a million dollars, but Parton paid up and left anyway. She commemorated their parting with “I Will Always Love You,” which she penned in one day, along with another No. 1 hit, “Jolene.”

Forgive me if you’ve heard this story before, but a profile of Dolly Parton just isn’t complete without it. Nearly 20 years before Houston covered “I Will Always Love You,” which would become the fifth best-selling single of all time, and drop a cool US$10 million into Parton’s pocket, the song found favour with the King himself. “Elvis loved the song and wanted to record it,” she wrote in her 2020 book, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics. “But his manager demanded half my publishing rights. It broke my heart, but I couldn’t give up my copyright.”

How does a 28-year-old up-and-coming songwriter say “thanks, but no thanks” to Elvis Presley? In Songteller, Parton credits her business savvy to her father, an illiterate tobacco farmer. “He knew how to barter; he knew how to bargain. … He knew exactly what everything was worth, and how much he was going to make from that tobacco crop.” What her father might have achieved, given the opportunity, would later inspire Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, a philanthropic literary initiative that has given 170 million books to children across five countries in 27 years. Parton has long insisted she’s neither proud nor ashamed of being born poor, and interestingly the same seems true for being rich. “I always wanted to be a success,” she tells me, “but to me success entails a whole lot of things. It’s not until you’ve made the money or made it big, it’s until you’re able to enjoy it.”

It’s all too easy to plot Parton’s accomplishments on a graph headed up, up, up. After shutting Elvis down, Parton topped the charts five times and earned her first Grammy Award before the end of the ’70s; she won the Country Music Association’s highest honour, Entertainer of the Year, in 1978; she signed a three-picture deal and transitioned seamlessly in 1980 into film with my old favourite, 9 to 5, collecting an Oscar nomination and a Grammy for Best Country Song. On the surface, all was swell.

Behind closed doors, monetary success made little difference and Parton fell into a deep depression in the mid-’80s. Physically, she was suffering from severe endometriosis that eventually required a hysterectomy and meant she’d never have a biological child. Emotionally, she pulled away from her husband and family, some of whom resented Parton for her success. Having received death threats — and with the pain of John Lennon’s 1980 assassination still raw — Parton cancelled her 1982 tour, retreated from public life and briefly considered suicide. “For about six months there I woke up every morning nearly dead,” she told Ladies’ Home Journal.

Then Parton packed up and went home again. Though her vast real estate holdings included a beachside Malibu house and apartments in Los Angeles and New York, the songstress chose Willow Lake, her secluded 25-hectare (63-acre) estate outside Nashville, to heal her soul. Parton spent weeks on end swimming, reading self-help books and strumming her guitar. She daydreamed of simpler times, specifically her childhood in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains near Pigeon Forge, Tenn.

In 1986, just 26 kilometres (10 miles) down the road from the house, where her family once lived, she built a meticulous re-creation of their one-room log cabin that would become the heart and soul of Dollywood, the theme park Parton had long imagined despite naysayers who opposed the grandiose idea. “I am prepared for success and braced for failure,” Parton once said, although the failure of Dollywood would have cost her an estimated US$50 million.

But you can’t win if you don’t play, so Parton rolled the dice. On opening day in May 1986, 12,000 fans filled Dollywood’s Main Street. Later that month, traffic queued for 10 kilometres (six miles) along the highway. Even today, Dollywood attracts more than 3 million pilgrims annually and employs more than 4,000 workers in Pigeon Forge.

I like to think the unlikely success of the fantastical Dollywood — which has a butterfly in flight as its logo, a wink to the power of transformation — is the moment Parton proved she was a businesswoman with vision. In 2021, she made Forbes magazine’s list of America’s richest self-made women, with an estimated net worth of US$350-million. “Just because you’re famous doesn’t necessarily mean you can build a brand around you,” Krakower explains. “There needs to be talent, personality, authenticity, resonance across multiple categories and with a wide demographic.”

Although Parton prefers to say she is grateful for her good fortune, glimpses of her business strategy are there should you seek them. For a Squarespace ad during last year’s Super Bowl, for example, Parton reimagined her famed “9 to 5” song with a little ditty designed to encourage those who want to turn side hustles into legitimate businesses. “Working 5 to 9, making something of your own now/And it feels so fine to build something from your know-how/Gonna move ahead and there’s nothing that you can’t do/When you listen to that little voice inside you.” Parton alluded to the power of that inner voice in the 2019 Netflix special Dolly Parton’s Heartstrings. “Other people didn’t always believe in me, and in those times I had to believe in myself,” she says. Then, realizing she’s being pretty saccharine, she pivots devilishly: “Plus nothing’s better than proving people wrong.”

This is the thing about Parton. Every time I think I understand her, the script flips. For example, as I gush over a list of accolades and accomplishments — 25 No. 1 singles on Billboard’s Country chart, 10 Grammy Awards, and soon-to-be six-time bestselling author — she begins with a canned celebrity response. “It’s all a great compliment any time I get honoured for anything.” The minute I buy this familiar phrase, she yanks the rug from under me. “But I don’t think I’m all that.”

In the Dollyverse, everything is itself and also its opposite. Parton is at once an open book and notoriously private, somehow both rich and poor, and claimed by both Republicans and Democrats, even though she’s never publicly picked a side. She’s AnnieLee Keyes and Ruthanna Ryder from Run, Rose, Run. Her whole persona is over-the-top performance art and completely authentic. As the old Dollyism goes, “a rhinestone shines just as good as diamond.”

I haven’t even told her how “I Will Always Love You” is the only song I can play on the piano, and I’m just getting around to asking Parton about “9 to 5” when the Dollyclock dings and Dollytime is up, having passed at warp Dollyspeed. I still have so many big questions and no clear answers, but I do have a memory I will cherish of my brief time with the enigmatic superstar. As promised, it’s been minimum Dolly time, maximum Dolly exposure.