Architectural treasure box

Winnipeg’s rich design culture attracts aficionados the world over.

At the turn of the 20th century, Winnipeg was primed to be a Canadian powerhouse. “There was more construction happening here in 1904 than there was in Toronto and Montreal combined,” says local architect Brent Bellamy, architecture columnist with the Winnipeg Free Press. Then the third-largest city in Canada, the gateway to Canada’s West boasted some amazing architectural feats: the coun- try’s tallest building and first skyscraper; the highest flagpole in the British Commonwealth; the Union train station designed by Warren and Wetmore, famous for New York’s Grand Central; and two dozen rail lines converging near the country’s most famous intersection (“Portage and Main, 50 below,” sing Neil Young and Randy Bachman, aptly, in Prairie Town).

But tough times arrived with the First World War. “Besides the war, there was the building of the Panama Canal—which changed shipping so you didn’t have to go through Winnipeg to get to Vancouver or California—and then the Depression,” says Bellamy. “A triple whammy stopped Winnipeg in its tracks.” While booming cities bulldozed over their past, 50 years of slow development left Winnipeg’s architectural heyday a perfectly preserved empty canvas for the Modernists.

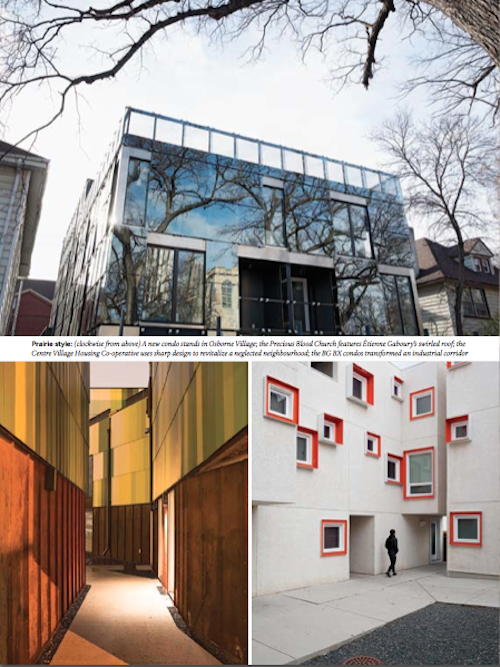

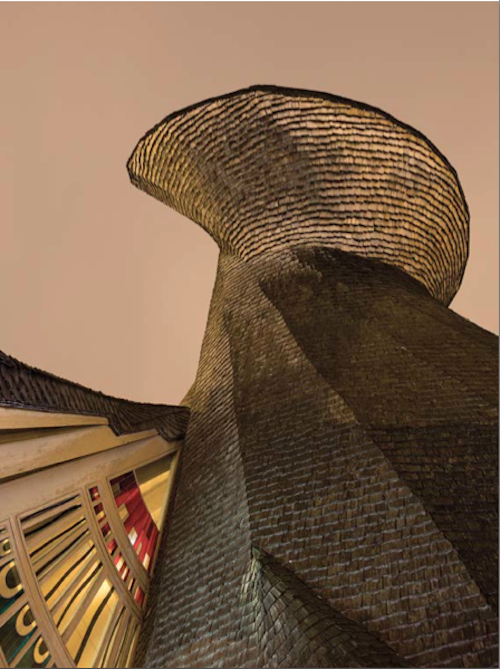

Built in the ’50s and ’60s, just south of Portage Avenue atop land retained by the Hudson’s Bay Company following the sale of Rupert’s Land, is a strip of North America’s finest collection of Modernist masterpieces. Bookended by Union Station and the Manitoba Legislative Building, the prestigious Broadway is so rich with architectural history that aficionados from all over the world visit for walking tours, where Winnipeg’s surplus of architecture in a relatively small space makes a century’s worth of art and design as awe-worthy as it is accessible. Among many can’t-miss Modernist marvels is the Winnipeg Art Gallery, with jutting pale stone that invokes the prow of a ship, the glassed triangular Royal Canadian Mint standing in stark contrast to the prairies around it, and the unmistakable Precious Blood Church, where Étienne Gaboury’s swirled roof, from below, looks like a winding path into heaven.

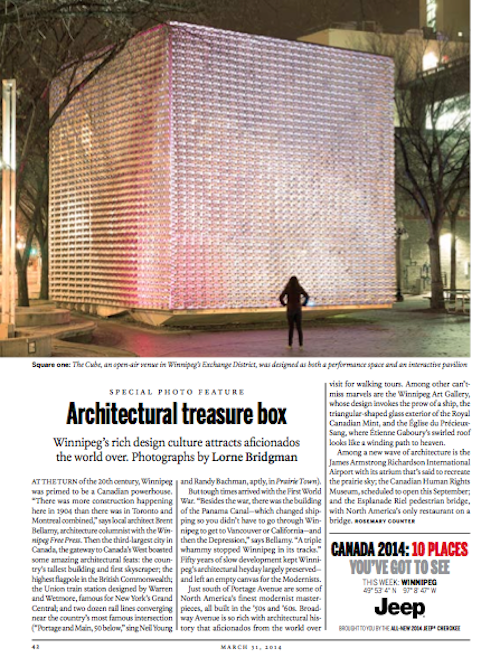

While classic buildings are protected, Winnipeg simultaneously forges into the future. Among a new wave of architecture is the James Armstrong Richardson International Airport, already named the world’s most iconic by the Travel Channel for its oversized atrium said to recreate the prairie sky, the steel-curtained Cube, which folds up and in to create an ever-changing stage for performers, and the Esplanade Riel pedestrian bridge, complete with North America’s only restaurant on a bridge. “I wouldn’t say it’s a boom, but maybe a mini-renaissance,” says Bellamy of Winnipeg’s continued status as a haven of experimentation and innovation. Then and now, Winnipeg as a must-see Canadian architectural treasure reigns supreme.