B.C.’s ‘Tropical Valley’

Liard River evokes a veritable Garden of Eden, albeit Northern-style

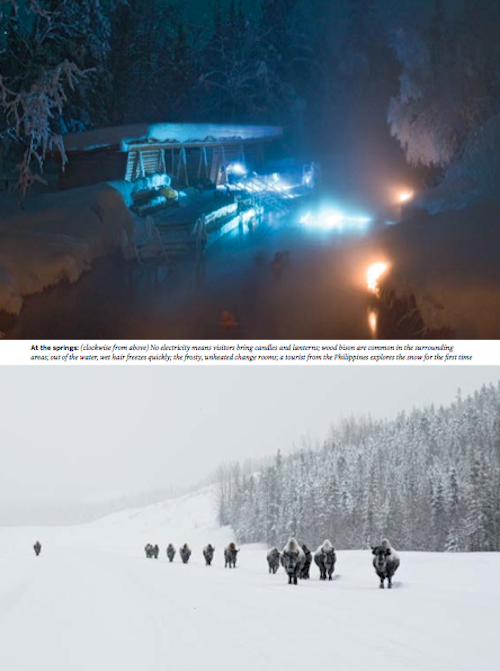

On the border of British Columbia and the Yukon, at kilometre 799 of the Alaska Highway, is a small town on a large river, both named Liard River. Abandoned as a trade route to the Yukon in 1870, the river’s rapids deemed too treacherous, the settlement’s population has dwindled to just 100 inhabitants. Meanwhile, just as native Peace Liard Indian tribes did for thousands of years, visitors flock to what many consider to be the premier location on the entire highway: Liard River Hot Springs Provincial Park, 10 km of lush spruce boreal forest, and home to the second-largest hot springs in Canada.

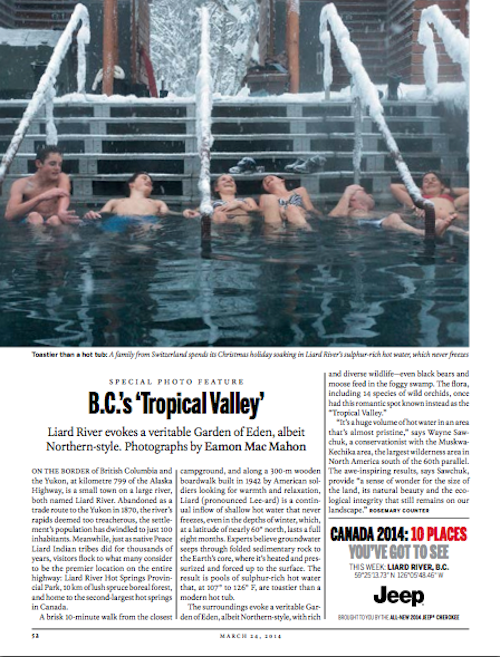

A brisk 10-minute walk from the closest campground, and along a 300-m wooden boardwalk built in 1942 by American soldiers looking for warmth and relaxation, Liard (pronounced Lee-ard) is a continual inflow of shallow hot water that never freezes, even in the depths of winter, which, at a latitude of nearly 60° north, lasts a full eight months. Experts believe groundwater seeps through folded sedimentary rock to the Earth’s core, where it’s heated and pres- surized and forced up to the surface. The result is pools of sulphur-rich hot water that, at 107° to 126° F, are toastier than a modern hot tub.

The surroundings evoke a veritable Garden of Eden, albeit Northern-style, with rich and diverse wildlife—even black bears and moose feed in the foggy swamp. The flora, including 14 species of wild orchids, once had this romantic spot known instead as the “Tropical Valley.”

“It’s a huge volume of hot water in an area that’s almost pristine,” says Wayne Sawchuk, a conservationist with the Muskwa-Kechika area, the largest wilderness area in North America south of the 60th parallel. The awe-inspiring results, says Sawchuk, provide “a sense of wonder for the size of the land, its natural beauty and the ecological integrity that still remains on our landscape.”