Deep Impact

With its rolling terrain and wide bays, Charlevoix is as ‘intoxicating as champagne.’

When David Mancini, an American from Philadelphia, went to fulfill his dream of running a quaint B & B in the sleepy countryside of Quebec, he did his research: “Of course I looked for the most beautiful place in the province, but also at tourist numbers and occupancy rates,” he says. It is no coincidence that they are one in the same; the region of Charlevoix, along the north shores of the St. Lawrence amid the Laurentian Mountains, is widely known as the original resort area in Canada, its inhabitants the inventors of hospitality.

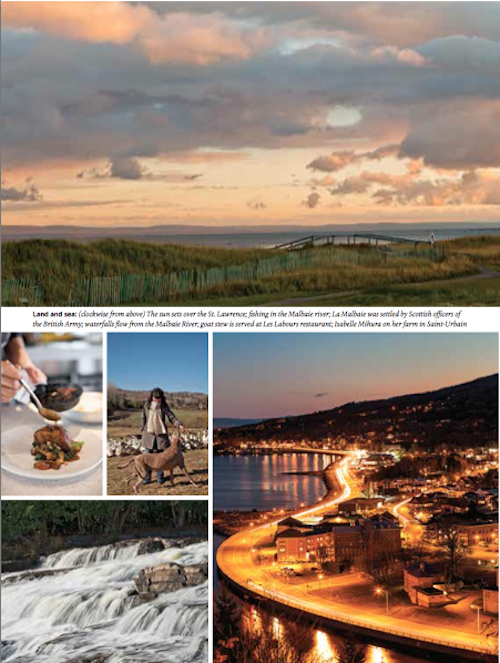

Attracted to gorgeous scenery of rolling terrain, fjords and wide bays—all within the Charlevoix crater, where a 15-billion tonne meteorite collided with the earth 360 million years ago—Scottish officers of the British Army built grand manors along the shore as early as 1760. Their settlement, now the seat of the judicial district in Charlevoix, was La Malbaie. Centuries before travel was commonplace, Charlevoix hosted international guests with ease. Word of mouth made Charlevoix a favourite with North America’s high society and wealthy Americans, including future president William Howard Taft, who built his “summer White House” on the outskirts. He described the effect of the fresh air as “intoxicated like champagne, but without the headache of the morning after.”

Then and now, a dozen villages dot the banks of the St. Lawrence, each more picturesque than the last: Petite-Rivière-Saint-François, Charlevoix’s gateway marks the site of the region’s oldest settlement; Saint-Irénée, home of Charlevoix’s annual International Music Festival, in Domaine Forget; L’Isle-aux-Coudres, a 15-minute ferry ride away, where cyclists ride a 26-kilometre road that encircles the island; and Baie-Saint-Paul, where David Mancini found his dream—a four-bedroom fixer-upper built in 1880.

The Gîte TerreCiel B & B sits in front of a wide stream so clean you can swim in it. Pop in a kayak for a five-minute row to the St. Lawrence. For nearly four years, Mancini has run both the inn and the kitchen—he bakes his own bread daily using flour from a local mill, serves it with homemade jams and juice. Visitors to Charlevoix, he adds, are much the same as they always were. Sixty per cent of his business comes from France, paying in bitcoins for their convenience, and there are no fixed rates. “During the winter, fall and spring, visitors are welcome to pay whatever they like,” says Mancini. Nobody has chosen zero yet, but it’s fine by him if they do. “I imagine, a long time ago, people would travel from village to village leaving whatever they could.” It is a fine nod to Charlevoix as the grandfather of Canadian tourism, still strong in old age.