They grow up so fast

The latest research on a baby’s remarkable brain development, from recognizing right and wrong to the gift of memory

While it seems all they do is cry and poop and feed and sleep, your baby’s brain is working far harder than yours—and neuroscientists are paying attention. Here’s the newest research on a baby’s remarkable brain development before the tender age of four.

In the womb: Even before the first breath, the fetal brain is forming all its main structures and creating synapses among its 100 billion nerve cells. But because it is undergoing such major construction, it is susceptible to neurodevelopmental disorders. Society talks much of alcohol and sushi, but an often-overlooked culprit of long-term effects on the baby brain is a more mundane and common influence: maternal stress. “Infants who are highly stressed [because their mothers are] highly stressed during pregnancy end up with measurably smaller brains,” says Dr. Jean Wittenberg, head of the infant psychiatry program at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Excess cortisol and adrenalin, produced by the body in response to stress, “damage vital regions—such as the hippocampus and amygdala—areas responsible for learning, memory and emotional responses,” according to a report from Harvard University’s National Scientific Council of the Developing Child.

Birth: “People don’t talk about birth as a milestone,” explains David Dyment, clinical geneticist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, “but even then, at time zero, there are expectations—movement, sucking, balance between wakeful moments and sleep.” Getting there takes time. New research from Columbia University Medical Center using data from school-age children in New York found that the longer a baby stays in the womb, the better the likelihood of academic achievement. Compared to those born at 41 weeks, babies born at 37 weeks were a third more likely to have reading difficulty and 19 per cent more likely to have problems doing math. For Dyment, this makes sense: “Certainly, a child born prematurely is at greater risk for medical conditions, including bleeding in the brain, which may cause developmental issues.” Dr. Stephen Miller, head of neurology at the Hospital for Sick Children, thinks birth age might be the most important: “If you’re looking for a single predictor of how well a baby will do, look at their gestational age of birth.”

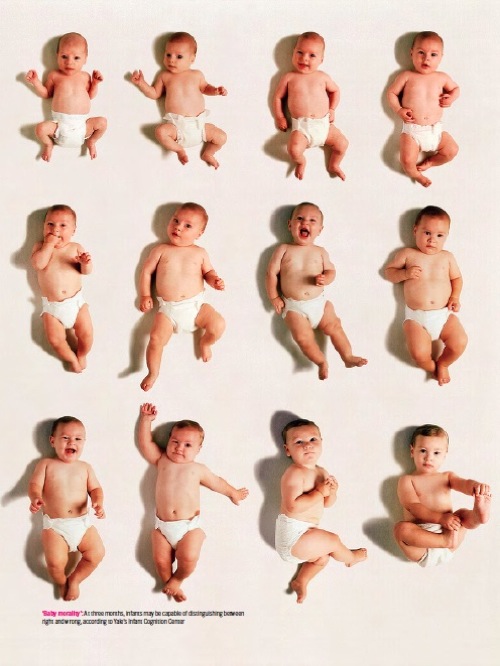

3 months: Now smiling and waving arms and legs around, baby is showing the first signs of personality. It may, according to psychologist Karen Wynn at Yale’s Infant Cognition Center, be capable of distinguishing between right and wrong. In a 2011 experiment, babies watched a puppet show: As one puppet struggled to remove a toy from a box, a nice puppet helped out. In a repeat scene, a mean puppet slammed the box shut. Given the choice, more than three-quarters of five-month-olds chose the good puppet. Wynn tried the same experiment on three-month-olds, who voted with their eyes. “Babies, even at three months, looked toward the nice character and looked hardly at all toward the unhelpful character,” Wynn explained in a 60 Minutes segment that aired last year. Critics were quick to poke holes in her theory of “baby morality”—babies had already watched Mom and Dad helping them for three whole months—but Wynn seemed convinced. “Study after study after study, the results are always consistently babies feeling positively toward helpful individuals in the world,” she said.

6 months: Good news for baby, not so good for parents: “By six months, babies can’t be soothed by people who are not their primary caregivers,” says Dr. Wittenberg at Sick Kids. For some, this represents the root of “baby consciousness”—the moment baby can recognize himself as different from other people, and that those people are different from each other. Consciousness is a relative and subjective term, but in April, French researchers sought to measure the pattern of consciousness—that is, a sensory cue followed by a spike in electrical activity—in babies as young as five months via baby-sized EEG caps. Two-thirds of squirmy subjects refused to co-operate, but the remaining 80 revealed the same pattern as adults, albeit slower. It took babies 1.3 seconds to recognize an unfamiliar face, whereas adults can do the same in 0.3 seconds.

9 months: Before the nine-month mark, point your finger at a baby and she will look at your finger; after nine months, she’ll look where you’re pointing. “Baby can recognize now that there’s an intention,” says Wittenberg. More fascinating, however, is that she may actually feel it. Since 2009, researchers at the University of London have used electrodes to record nine-month-old brains as they watched people reach for toys. The babies’ motor region was activated as if they themselves were doing the reaching. This suggests predictive behaviour, or that “they observe or anticipate other people’s actions, even when these are actions they cannot yet do themselves,” explains lead researcher Victoria Southgate. “This mechanism is crucial for collaborative activity with others,” she adds. Which really means that playtime just became more fun.

1 year: By one year, the brain has nearly doubled in size. Neural connections are strengthening, so some eager parents start to fine-tune baby’s future skills. They’re not wrong: Researchers at McMaster University in Hamilton found very early musical training led to one-year-olds who communicated better (through pointing and gesturing), smiled and soothed more and showed larger and earlier brain responses to sound. The study compared infants who took interactive music classes between six and 12 months (which included singing lullabies and playing percussion) with infants who attended classes where music merely played in the background. “Past studies of musical training have focused on older children,” says Laurel Trainor, director of the McMaster Institute for Music and the Mind. “Our results suggest that the infant brain might be particularly plastic with regard to musical experience.” Others aren’t persuaded (and baby music lessons will not guarantee you’ve got a budding musician): “Do babies understand beats and timing? No,” says Dyment. “But can they recognize music and have favourite songs? Absolutely.”

18 months: In a 2011 TED conference talk, developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik described her findings of “the broccoli-Goldfish” study. Gopnik placed two bowls—one of tasty Goldfish crackers, one of raw broccoli—in front of 15- and 18-month-olds. All babies preferred the crackers. Then a researcher made yummy noises as she eyed the veggies, before putting out her hand and asked for food. “The question is: What would the babies give her? What they liked or what she liked?” Eighteen-month-olds shared the broccoli, despite their preference for crackers. (Fifteen-month-olds, meanwhile, stared blankly, then offered up the crackers just the same.) At 18 months, says Gopnik, “babies discover this really profound fact about human nature: We don’t always want the same thing. And what’s more, they felt they could do things to help others get what they want.”

2 years: By age two, the brain is about 80 per cent of its adult size and is already strengthening well-used connections and eliminating others. “You get this pruning effect of connections between neurons, which will continue until adolescence,” says Dyment. You also get the gift of memory. Experts once scoffed at memories before age three or four—when the hippocampus is adequately formed—but new research challenges that. In a 2011 New Zealand study, 46 kids as young as two played happily with a “magic shrinking machine,” where a pulled lever turned full-sized toys into smaller versions (memorable, for a kid). Six years later, most had forgotten the whole event, but nine had strong recollections, two of those from children barely two at the time. A longitudinal study at Memorial University in Newfoundland asked 140 children between four and 14 to describe their earliest memories. Two years later, they asked again. “Younger children’s earliest memories seemed to change, with memories from younger ages being replaced by memories from older ages,” says psychology professor Carole Peterson, who led the study. “But older children became more consistent in their memories as they grew older.”

3 years+: Just a year away from full size, the brain has experienced what Sick Kids neurologist Dr. Miller calls “an explosion of development.” His Sick Kids colleague Dr. Margot J. Taylor cautions that “not all children reach their milestones on time, and how can we tell ahead of time which children will require extra help to stay on track?” To do so, Taylor’s team has been following a group of pre-term infants (born two or more months early) up to age four, comparing brain imaging at birth to ongoing behaviour, cognitive and language assessments. Preliminary results suggest that changes in the brain detectable at birth may be correlated with developmental difficulties four years later, so early intervention may aid in social and motor skills, expression of needs and desires and enhanced academic success. “Looking at the developing brain can help us identify the most vulnerable children before their difficulties come to light,” she says.