Hope is in the eye of the beholder

After decades of on-the-ground reporting, Sally Armstrong has concluded that women’s conditions are improving.

“Now, at last, is the time for women,” declares Sally Armstrong, Canadian journalist – and teacher and activist, three-time Amnesty International Award winner, member of the Order of Canada – in her new book, Ascent of Women. Globalization has made female emancipation not just an inevitability, but an economic necessity: “The world can no longer afford to oppress half its population,” she writes.

It’s a popular theme that shows no sign of slowing: Hanna Rosin’s The End of Men analyzed women’s new dominance of academia and economics; Caitlin Moran was labelled “the new face of feminism” after the publication of her essays in How to Be a Woman; and Madeleine M. Kunin’s The New Feminist Agenda explored a new revolution of women and work.

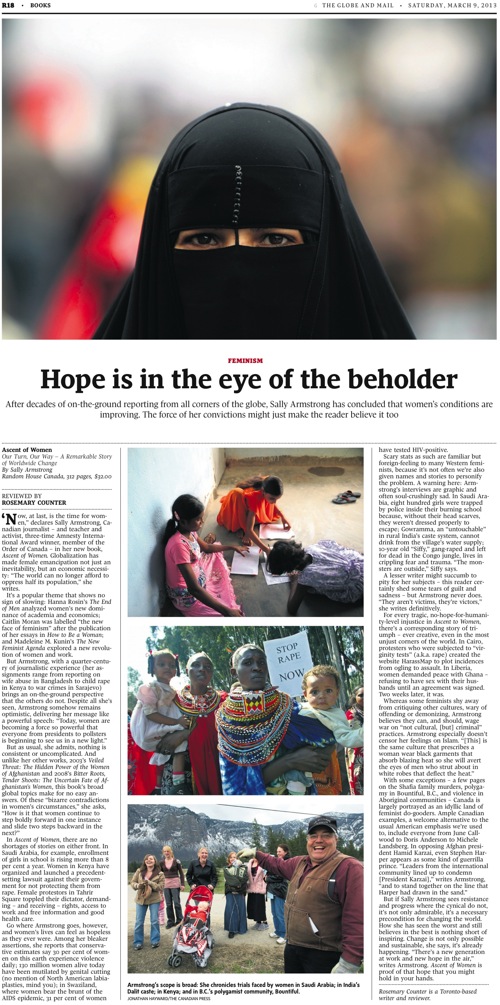

But Armstrong, with a quarter-century of journalistic experience (her assignments range from reporting on wife abuse in Bangladesh to child rape in Kenya to war crimes in Sarajevo) brings an on-the-ground perspective that the others do not. Despite all she’s seen, Armstrong somehow remains optimistic, delivering her message like a powerful speech: “Today, women are becoming a force so powerful that everyone from presidents to pollsters is beginning to see us in a new light.”

But as usual, she admits, nothing is consistent or uncomplicated. And unlike her other works, 2003’s Veiled Threat: The Hidden Power of the Women of Afghanistan and 2008’s Bitter Roots, Tender Shoots: The Uncertain Fate of Afghanistan’s Women, this book’s broad global topics make for no easy answers. Of these “bizarre contradictions in women’s circumstances,” she asks, “How is it that women continue to step boldly forward in one instance and slide two steps backward in the next?”

In Ascent of Women, there are no shortages of stories on either front. In Saudi Arabia, for example, enrollment of girls in school is rising more than 8 per cent a year. Women in Kenya have organized and launched a precedent-setting lawsuit against their government for not protecting them from rape. Female protestors in Tahrir Square toppled their dictator, demanding – and receiving – rights, access to work and free information and good health care.

Go where Armstrong goes, however, and women’s lives can feel as hopeless as they ever were. Among her bleaker assertions, she reports that conservative estimates say 30 per cent of women on this earth experience violence daily; 130 million women alive today have been mutilated by genital cutting (no mention of North American labiaplasties, mind you); in Swaziland, where women bear the brunt of the AIDS epidemic, 31 per cent of women have tested HIV-positive.

Scary stats as such are familiar but foreign-feeling to many Western feminists, because it’s not often we’re also given names and stories to personify the problem. A warning here: Armstrong’s interviews are graphic and often soul-crushingly sad. In Saudi Arabia, eight hundred girls were trapped by police inside their burning school because, without their head scarves, they weren’t dressed properly to escape; Gowramma, an “untouchable” in rural India’s caste system, cannot drink from the village’s water supply; 10-year old “Siffy,” gang-raped and left for dead in the Congo jungle, lives in crippling fear and trauma. “The monsters are outside,” Siffy says.

A lesser writer might succumb to pity for her subjects – this reader certainly shed some tears of guilt and sadness – but Armstrong never does. “They aren’t victims, they’re victors,” she writes definitively.

For every tragic, no-hope-for-humanity-level injustice in Ascent to Women , there’s a corresponding story of triumph – ever creative, even in the most unjust corners of the world. In Cairo, protesters who were subjected to “virginity tests” (a.k.a. rape) created the website HarassMap to plot incidences from ogling to assault. In Liberia, women demanded peace with Ghana – refusing to have sex with their husbands until an agreement was signed. Two weeks later, it was.

Whereas some feminists shy away from critiquing other cultures, wary of offending or demonizing, Armstrong believes they can, and should, wage war on “not cultural, [but] criminal” practices. Armstrong especially doesn’t censor her feelings on Islam. “[This] is the same culture that prescribes a woman wear black garments that absorb blazing heat so she will avert the eyes of men who strut about in white robes that deflect the heat.”

With some exceptions – a few pages on the Shafia family murders, polygamy in Bountiful, B.C., and violence in Aboriginal communities – Canada is largely portrayed as an idyllic land of feminist do-gooders. Ample Canadian examples, a welcome alternative to the usual American emphasis we’re used to, include everyone from June Callwood to Doris Anderson to Michele Landsberg. In opposing Afghan president Hamid Karzai, even Stephen Harper appears as some kind of guerrilla prince. “Leaders from the international community lined up to condemn [President Karzai],” writes Armstrong, “and to stand together on the line that Harper had drawn in the sand.”

But if Sally Armstrong sees resistance and progress where the cynical do not, it’s not only admirable, it’s a necessary precondition for changing the world. How she has seen the worst and still believes in the best is nothing short of inspiring. Change is not only possible and sustainable, she says, it’s already happening. “There’s a new generation at work and new hope in the air,” writes Armstrong. Ascent of Women is proof of that hope that you might hold in your hands.